Digitalizing ASEAN (2): Three Key Pillars

In the second of two-series article, we introduce ASEAN Youth Initiative Empowerment Programme, a one-week program for ASEAN Youth organized by ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada. The theme of […]

Digitalizing ASEAN (1): What It is and Why It is Important

In this first series of article, we introduce ASEAN Youth Initiative Empowerment Programme, a one-week program for ASEAN Youth organized by ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada. The theme of […]

ASEAN Economic Community: In Search of a Single Production Base

A key motivation behind the pursuit of a comprehensive ASEAN Economic Community is to establish a single production base. By doing so, ASEAN member states hope to increase their competitiveness, […]

Marawi’s Crisis Requires ASEAN’s Centrality, Not External Intervention

Since the past two weeks, Southeast Asia has been putting a serious concern to its security and stability caused by the state of crisis in Marawi and Mindanao. Isnilon Hapilon, […]

ASEAN Summit 2017: A Conclusion to South China Sea?

In April this year, the ASEAN Summit kicked off at the heart of the Philippines – Metro Manila. With the theme entitled “Partnering for Change, Engaging the World”, this summit […]

Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI) and the New Politics of Regionalism in Southeast Asia

China officially launched the Belt and Road Initiatives on May 2017. Attended by 29 partner countries (with the absence of some prominent neighbours such as India), the launching of the […]

UAE-ASEAN Relations: Beyond “Emirates’ Diplomacy”?

In the past several years, there is an increasing tendency among the countries of the Gulf to direct their foreign policies towards the growing economies of Asia. Despite relatively unreported, […]

‘Brexit’, the European Union, and the ‘Communication Deficit’: A Lesson for ASEAN

‘Brexit’ has created shockwaves through the European Union and called into question whether regional integration is sustainable, and ASEAN is watching developments closely. A key issue that ASEAN must learn […]

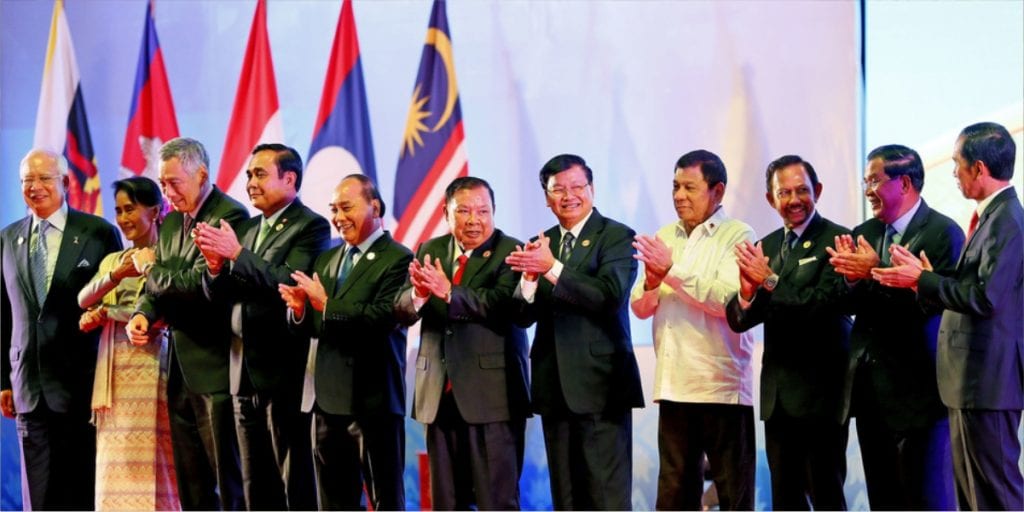

Has ASEAN Moved Away from ZOPFAN?

From April 26-29, Manila hosted the 30th ASEAN Summit. The summit is expected to make progress on the current geopolitical crisis which affects the Southeast Asian region. Among the rests, […]

Why ASEAN Needs to Regulate Land and Water Grabbing Issues

Political stability and food security are inter-related both at national and regional level. The distortion of political instability would eventually affect food availability and distribution. On the one hand, food […]