What’s Missing in the AHRD?: Synergizing with Civil Society Towards Better Human Rights Regime in ASEAN

Written by Gerald John C. Guillermo

Civil society has long been a bastion of service and advocacy—contributing to the development and uplifting of lives, particularly in marginalized and underprivileged sectors of society. The Southeast Asian region is a testament to the catalytic role that civil society plays in lobbying for positive sociopolitical and economic changes, most especially in human rights protection (Tadem, 2017). During the COVID-19 pandemic, civil society organizations (CSOs) have supported efforts to curb the effects of the pandemic, especially for the vulnerable and marginalized. Those CSOs involved in human rights and democratization have faced more constraints in operation and activities prior to the pandemic, but many have continued their advocacy to hold their government accountable (Nixon, 2020).

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has embraced a shift toward a “people-oriented” approach, aiming to widen participation in civil society but restricting engagement which includes the establishment of an accreditation system and participation in informal consultations for CSOs (Gerard, 2014). Moreover, strict restrictions on the nature of participation and a limited set of issues up for discussion narrow cooperation with CSOs further, which results in discouraging participation from human rights-based CSOs. Therefore, the civic society narratives in ASEAN-sanctioned spaces are limited and controlled.

This is particularly true with the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (AHRD). The AHRD has been criticized for being a context-dependent human rights document subject to laws, local principles, and customs. In fact, during its declaration, various civil society organizations denounced the AHRD and that it “falls far below international standards” by undermining the universality of human rights principles (Article 19, 2012). Furthermore, the drafting process was controversial, such that CSOs were primarily excluded from the drafting process except for carefully managed “consultations” and representatives were still accountable to their government (Renshaw, 2013; Davies, 2014). The exclusion of civil society in the drafting process of the AHRD illustrates the limited effectiveness of CSOs’ advocacy in having an actual human rights protection mechanism in the ASEAN (Gomez & Ramcharan, 2012).

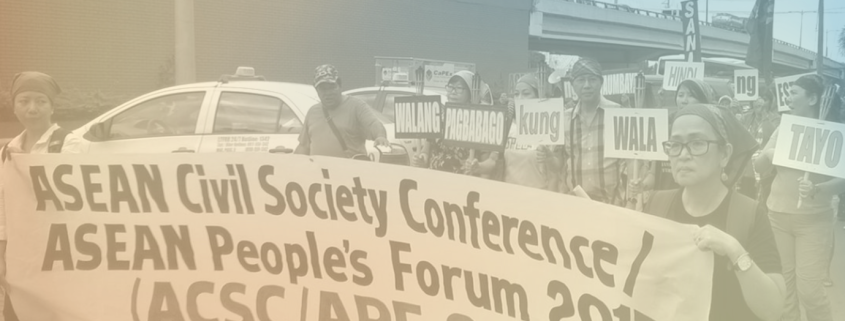

However, civil society has moved forward and beyond the broken dynamics between CSOs and official ASEAN processes. For instance, CSOs all over the ASEAN region has maintained a robustly critical stance toward the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR) in its tenth year of founding and challenge them together with ASEAN to improve on acting on rights abuses (Hanara, 2019 & Forum Asia, 2019, as cited in Langlois, 2021). Moreover, in response to constraints on civil society participation, CSOs have developed “created spaces,” i.e., pursuing a political activity that bypasses regional and state actors such as with ASEAN-sanctioned modes of engagement and political arenas such as parallel activities, protests, and production and dissemination of critical knowledge (Jayasuriya & Rodan, 2007, as cited in Gerard, 2014) and supported by external actors (Sundrijo, Awigra, Safitri, Virajati, & Wening, 2020).

While this seems as if parting ways between one of the moving spirits of the human rights agenda in the region, i.e., the civil society and the ASEAN, it is not the be-all and end-all scenario. There are ways for ASEAN to catch up to its commitment to human rights and live up to being “people-centered.” To develop and establish an institutional and normative human rights framework in the region, formal and genuine consultation mechanisms with the CSOs must be in place, which includes the establishment of formal complaints mechanisms in AICHR, expansion of the accreditation process for CSOs, particularly for human rights based CSOs, (Jones, 2019) and review of the effectiveness of the AHRD.

The issues confronted by the Southeast Asian region, as surfaced in the recently concluded 40th and 41st ASEAN Summits, such as climate change, economy, peace, and security, are to be viewed not only at the state level but also in spaces where it matters—at the ground level. Recognizing the role of CSOs in helping solve such issues is one thing but engaging them more genuinely is another. ASEAN must support on-the-ground efforts of CSOs to mainstream human rights and connect networks of CSOs to promote understanding of particular issues with various stakeholders.

Moreover, external organizations and stakeholders must support efforts for civil society to integrate and synergize with the broader organization of ASEAN. With ASEAN welcoming more external partners to pursue areas of cooperation, such international stakeholders must steer the discussion in crafting a more inclusive human rights regime in the region with the help of CSOs.

Indeed, CSOs in the ASEAN region have been growing both in quantity and quality, constructively contributing to regionalism and strategically maneuvering against the institutional state-centrism of ASEAN through less structured mechanisms (Sundrijo et al., 2020). While CSOs have the means to navigate this “road less traveled,” it should not be that way. ASEAN must genuinely open its arms and confront the complex issue of human rights and “living” the AHRD, facing not only government dignitaries but listening to real people, real stories, and real lives, particularly the marginalized and the oppressed.

*The views expressed in this article do not represent any of the organizations with which the author is affiliated.

About Writer:

- Gerald John C. Guillermo is a Juris Doctor student at the University of the Philippines College of Law. He received his Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science, with a Minor Degree in Development Management at the Ateneo de Manila University. His areas of skills and interests include youth, public policy, international relations, governance, and law. Contact information: geraldjohnguillermo@gmail.com.

Bibliography

- Article 19. (2012). Civil Society Denounces Adoption of Flawed ASEAN Human Rights Declaration: AHRD falls far below international standards. https://www.article19.org/data/files/medialibrary/3536/Civil-Society-Denounces-Adoption-of-Flawed-ASEAN-Human-Rights-Declaration.pdf

- Davies, M. (2014). An Agreement to Disagree: The ASEAN Human Rights Declaration and the Absence of Regional Identity in Southeast Asia. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 33(3). 107–129. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/186810341403300305

- Gerard, K. (2014). ASEAN and civil society activities in ‘created spaces’: The limits of liberty, The Pacific Review, 27:2, 265-287, https://doi.org/doi:10.1080/09512748.2014.882395

- Gomez, J. & Ramcharan, R. (2012). ASEAN needs formal civil society engagement mechanism on human rights. Asia Centre. https://asiacentre.org/asean-needs-formal-civil-society-engagement-mechanism-on-human-rights/

- Jones, D. (2019). ASEAN’S Human Rights Conundrum: An Analysis Of The Failures Of The ASEAN System For Promoting Human Rights (Bachelor’s dissertation). https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1035&context=ppe_honors

- Langlois, A. (2021). Human rights in Southeast Asia: ASEAN’s rights regime after its first decade. Journal of Human Rights, 20(2), 151-157. https://doi.org/doi:10.1080/14754835.2020.1843144

- Nixon, N. (2020). Civil Society in Southeast Asia During the Covid-19 Pandemic. The Asia Foundation. https://asiafoundation.org/publication/govasia-issue-1-civil-society-in-southeast-asia-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

- Renshaw, C. (2013). The ASEAN Human Rights Declaration 2012. Human Rights Law Review, 13(3), 557-579. https://doi.org/doi:10.1093/hrlr/ngt016

- Sundrijo, D. A., Awigra, D., Safitri, D., Virajati, K., & Wening, P.P.P. (2020). Civil Society Participation in ASEAN Regionalism Strengthening the Capacity of ACSC/APF to Advocate the Interest of the People of Southeast Asia. Human Rights Working Group. https://www.hrwg.or.id/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Civil-Society-Participation-in-ASEAN-draft-2.pdf

- Tadem, E. (2017). New Perspectives on Civil Society Engagement with ASEAN. Heinrich Böll Stiftung. https://th.boell.org/en/2017/07/12/new-perspectives-civil-society-engagement-asean#_ftn2

Photo by American Public Power Association on Unsplash

Photo by American Public Power Association on Unsplash

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!