Written by: Ferdian Ahya Al Putra

Indonesia should be proud after successfully organizing the Asian Games and Asian Para Games in 2018. Now Indonesia is assigned to host the ASEAN Para Games 2022. ASEAN Para Games is the largest disability sports party or event in Southeast Asia (Kemenko PMK, 2022). This time, the ASEAN Para Games will be held on 30 July – 6 August 2022 in Central Java Province, including Solo City, Semarang City, Sukoharjo, and Karanganyar (Kemenpora, 2022).

Inside the ASEAN’s structure, they have ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Sport (AMMS). To support AMMS, ASEAN organized the Senior Officials Meeting on Sports (SOMS). In short, they agreed to assist AMMS in enhancing cooperation in sports or related activities towards balanced sports development in ASEAN; Promoting a healthier lifestyle among citizens of ASEAN Member States through sports, encouraging more interaction among peoples of ASEAN, thus fostering friendship among the ASEAN Member States, as well as contributing to ASEAN integration and community building; Advocating and promoting the role of sports in regional development, peace and stability; and Promoting sportsmanship, competitiveness and an ASEAN culture of excellence in sports at the regional and international levels (ASEAN, 2011). This ASEAN Para Games could be one of the programs they organized to achieve the objectives.

Sports Diplomacy Concept

The ASEAN Para Games can be used as momentum in introducing culture and tourism, especially in Solo or the cities around. This goal is closely related to the term sports diplomacy. In a review published by the European Union, it is understood that Sports Diplomacy is an aspect of public diplomacy, and it can be used as a soft-power tool for an increasing number of purposes (Murray & Prince, 2020). Murray also defined “Sports Diplomacy” as a new term that describes an old practice: the unique power of sport to bring people, nations, and communities closer together via a shared love of physical pursuits (Murray, 2020).

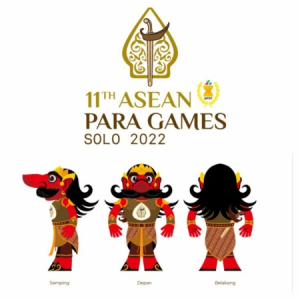

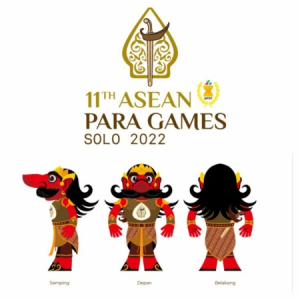

Based on this concept, it can be understood that sport can be a tool to achieve diplomatic goals. The 2022 ASEAN Para Games is an excellent opportunity to attract tourists, especially when Solo is the location for the event. As in Yogyakarta or Bali, both have strong cultural elements which are a big attraction for foreign tourists. Meanwhile, Solo is also a city with cultural tourism. In other words, this event is the right opportunity to introduce Solo to the international scene especially tourists who have come to watch the ASEAN Para Games. The packaging of the ASEAN Para Games this time also cannot be separated from the cultural elements attached to Solo. For example, the 2022 ASEAN Para Games logo also includes cultural elements, namely the illustration of ‘gulungan’ as part of the wayang, a Javanese puppet symbol. A dagger in the logo’s center further emphasizes the event’s cultural element. In addition to the logo, the committee also presented the Rajamala Mascot, which Rojomolo read according to the Javanese accent. Rajamala is known to be unrivaled and is symbolized as the power to resist evil or a negative aura. Rajamala is also a palace heirloom in the form of a can think that symbolizes the greatness of the Surakarta Palace (Jawapos, 2022). This shows that the committee is trying to push cultural diplomacy through sports.

Logo and Mascot of 11th ASEAN Para Games (Foto: Jawapos)

Logo and Mascot of 11th ASEAN Para Games (Foto: Jawapos)

Culture, Tourism, and Culinary in Solo

Talking about culture and tourism, Solo has various cultural sites worth visiting by both local and foreign tourists. In Solo, there are two symbols of royal history: Kasunanan Palace and Mangkunegaran Palace. The Giyanti Agreement signed in 1755 divided the Sultanate of Mataram into two powers, namely the Surakarta Sunanate and the Yogyakarta Sultanate (Darmawan, 2017). While the Mangkunegaran Palace is the place where the kings or dukes of Mangkunegaran reside. This palace was built by Raden Mas Said or Prince Sambernyawa, the founder of Mangkunegaran who holds the title Kanjeng Gusti Pangeran Adipati Arya (KGPAA) Mangkunegara I (Ningsih, 2021). In addition, tourists can visit other cultural sites as alternatives, such as the Heritage Batik Keris, the Press Monument, the Nusantara Keris Museum, and so on.

Furthermore, Solo has Batik industrial centers, especially in two Batik villages in the Laweyan and Kauman areas. As we all know, Batik is a world heritage site in Indonesia. The recognition of batik as a world heritage has been in effect since the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) established Batik as Masterpieces of the Oral and the Intangible Heritage of Humanity on 2 October 2009 (KWRI UNESCO, 2017). In addition to culture, Solo has various distinctive culinary delights with a high taste. The local culinary potential includes Nasi Liwet, Soto, Gudeg, Selat, Pecel, Timlo, Bestik, Tengkleng, and so on. Saeroji and Wijaya (2017) mention that Solo has great culinary potential. They mentioned, for example, that in the Banjarsari sub-district, there are 12 culinary destinations, in Serengan 7 culinary destinations, in Jebres 7 culinary destinations, six culinary destinations in Laweyan, and three destinations in the Kliwon market area. Therefore, visiting Solo is a good opportunity to get to know or buy Batik directly from the industrial center and become a unique attraction for tourists to taste its exceptional cuisine.

Festival in Solo: Solo Batik Carnival (Foto: Instagram/ solobatikcarnival_official)

Festival in Solo: Solo Batik Carnival (Foto: Instagram/ solobatikcarnival_official)

In other words, this time, the ASEAN Para Games can be an opportunity to introduce Solo’s culture and tourism. Sports expert at Universitas Sebelas Maret (UNS), Febriani Fajar Ekawati, M.Or., Ph.D., mentioned that the event has the potential to revive Solo’s economy. The two main sectors that will be affected by the implementation of the 2022 ASEAN Para Games are the industry and tourism sectors. She also mentioned that the benefits of the ASEAN Para Games for the tourism sector could occur in 2 types, tangible and intangible. The tangible benefit refers to the hotel sector that had fallen due to the pandemic, which will be booked for ASEAN Para Games athletes, coaches, and officials. The hotel is full of guests, and the shops around the hotel can also sell daily necessities and souvenirs. The guests will undoubtedly ogle the culinary sector.

Meanwhile, intangible in nature, namely the icon of Solo, will be worldwide. Several international media will report interesting things about Solo so that this city will be known to the broader world community (UNS Public Relations, 2022). This view is also supported by Solo’s mayor, Gibran Rakabuming, who stated that he wants Solo, a small city with a solid cultural background. The world can see how successful it is in organizing sporting events such as the Asean Para Games (Herdyanto, 2022). In addition, Solo is known as a ‘festival city’ where they already host various cultural festivals such as Solo Batik Carnival, Solo International Performing Arts, Festival Jenang (Traditional cuisine display), etc. This will also enhance the attractiveness of Solo itself.

Based on the concept above, the ASEAN Para Games can help the government to introduce Solo and its tourism to the international view. Relevant parties, from the government to the committee, it is essential to pay attention to the elements contained in the implementation, such as by displaying cultural elements in it or serving special cuisines from Solo for consumption for athletes, officials, journalists, and spectators. It is also important to distribute information about tourism and culinary in Solo along with access if a tourist wants to move from one place to another, for example, through information boards, social media or other digital platforms. This aims to reach the ASEAN pillar, namely the economic pillar, where one of the points to be encouraged is to optimize the tourism sector.

ASEAN Para Games, in this case, is not just a sports party. In a more social realm, this can be an opportunity to strengthen solidarity between ASEAN countries by upholding sportsmanship when competing. This is appropriate with Murray’s argument that sport can bring people and nations closer through sports competition. This is also a place to show off athletes with disabilities. This also emphasizes that sport can be inclusive, which means that everyone has the same opportunity to compete where the motto of this event is “Striving for Equality”. In this context, sport influences the relation among ASEAN members as the concept of sports diplomacy is mentioned. The most crucial point is upholding sportsmanship and fair play value at first, then it will be followed by how sport can strengthen engagement among the member countries of ASEAN.

About Writer

- Ferdian Ahya Al Putra is a Programme Intern at ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada. He finished his bachelor’s degree at the International Relations Department, Universitas Sebelas Maret, and his master’s degree at International Relations Department, Universitas Gadjah Mada. He is also an LPDP Scholarship Awardee from the Ministry of Finance, Republic of Indonesia. He can be contacted through email: ferdian.ahya.al@mail.ugm.ac.id or ferdianahya@gmail.com

Bibliography

- ASEAN. (2011). 4. Advocating and promoting the role of sports in regional development, peace and stability;;. ASEAN. Retrieved July 19, 2022, from http://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/TOR-of-SOMS.pdf

- Darmawan, J. (2017). Mengenal Budaya Nasional “Trah Raja-raja Mataram di Tanah Jawa”. Deepublish. https://books.google.co.id/books/about/Mengenal_Budaya_Nasional_Trah_Raja_raja.html?id=Xm85DwAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y

- Herdyanto, H. (2022, June 21). Wali Kota Solo Inginkan Asean Para Games 2022 Jadi Ajang Untuk Mendongkrak Budaya Solo di Pentas Dunia – Mitra News. Mitranews.net. Retrieved July 18, 2022, from https://www.mitranews.net/hot-news/pr-1053717389/wali-kota-solo-inginkan-asean-para-games-2022-jadi-ajang-untuk-mendongkrak-budaya-solo-di-pentas-dunia

- Humas UNS. (2022, February 9). Pakar Olahraga UNS Sebut ASEAN Para Games 2022 Berpotensi Bangkitkan Industri dan Pariwisata Solo. Universitas Sebelas Maret. Retrieved July 15, 2022, from https://uns.ac.id/id/uns-update/pakar-olahraga-uns-sebut-asean-para-games-2022-berpotensi-bangkitkan-industri-dan-pariwisata-solo.html

- Jawapos. (2022, June 10). Logo dan Maskot ASEAN Para Games 2022 Diluncurkan. Radar Solo. Retrieved July 19, 2022, from https://radarsolo.jawapos.com/sport/sport-nasional/10/06/2022/logo-dan-maskot-asean-para-games-2022-diluncurkan/

- Kemenko PMK. (2022, March 9). Indonesia Mantapkan Persiapan ASEAN Para Games 2022 | Kementerian Koordinator Bidang Pembangunan Manusia dan Kebudayaan. Kemenko PMK. Retrieved July 11, 2022, from https://www.kemenkopmk.go.id/indonesia-mantapkan-persiapan-asean-para-games-2022

- Kemenpora. (2022, July 6). 11th ASEAN Para Games 2022 Mengundang Putra-Putri Bangsa untuk Berkontribusi dan Mengasah Talenta melalui Program Volunteer. Kementerian Pemuda dan Olahraga. Retrieved July 11, 2022, from https://www.kemenpora.go.id/event/10/11th-asean-para-games-2022-mengundang-putra-putri-bangsa-untuk-berkontribusi-dan-mengasah-talenta-melalui-program-volunteer

- KWRI UNESCO. (2017, October 2). Hari Ini 8 Tahun Lalu, UNESCO Akui Batik sebagai Warisan Dunia Asal Indonesia. KWRI UNESCO. Retrieved July 15, 2022, from https://kwriu.kemdikbud.go.id/berita/hari-ini-8-tahun-lalu-unesco-akui-batik-sebagai-warisan-dunia-asal-indonesia/

- Murray, S. (2020, 27 October). Sports Diplomacy: History, Theory, and Practice. oxfordre.com. Retrieved July 2022, 19, from https://oxfordre.com/internationalstudies/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.001.0001/acrefore-9780190846626-e-542.

- Murray, S., & Prince, G. (2020, October 27). SPORT DIPLOMACY:. IRIS – Institut de Relations Internationales et Stratégiques. Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://www.iris-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/1-TES-D_LiteraryReview-of-a-scholarly-and-policy-recources.pdf

- Ningsih, W. L. (2021, October 10). Beda Keraton Surakarta dan Mangkunegaran Halaman all. Kompas.com. Retrieved July 15, 2022, from https://www.kompas.com/stori/read/2021/10/10/120000179/beda-keraton-surakarta-dan-mangkunegaran?page=all

- Padhi, S. D. S. A. a. F. 2. B. (2011, 1 January). Sports Diplomacy: South Africa and FIFA 2010. Insight of Africa, 3(1), 55-70. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0975087814411132

H.E. Deng Xijun believes that with the existing engagement and the development of the China-ASEAN Partnership, additional collaboration can be enlisted to promote scientific research and collaboration. Additionally, His Excellency is willing to hear ideas and support with the initiative. H.E. Deng Xijun expects the collaboration could arise several policy recommendations, particularly in terms of the Myanmar Resolution, and support the initial stages of research projects in terms of the studies on decision making during the ASEAN Summit as His Excellency concerned with the situation of Myanmar for the Indonesia ASEAN Chairmanship next year.

H.E. Deng Xijun believes that with the existing engagement and the development of the China-ASEAN Partnership, additional collaboration can be enlisted to promote scientific research and collaboration. Additionally, His Excellency is willing to hear ideas and support with the initiative. H.E. Deng Xijun expects the collaboration could arise several policy recommendations, particularly in terms of the Myanmar Resolution, and support the initial stages of research projects in terms of the studies on decision making during the ASEAN Summit as His Excellency concerned with the situation of Myanmar for the Indonesia ASEAN Chairmanship next year. To wrap up the visit, H.E. Deng Xijun and the staffs were invited to visit the Center’s office in FISIPOL BC Building 2nd Floor Suites 208 and 209. In the office, H.E. Deng Xijun, Dr. Dafri Agussalim, Mrs. Yulida Nuraini Santoso, and others had a brief discussion about future institutional collaboration.

To wrap up the visit, H.E. Deng Xijun and the staffs were invited to visit the Center’s office in FISIPOL BC Building 2nd Floor Suites 208 and 209. In the office, H.E. Deng Xijun, Dr. Dafri Agussalim, Mrs. Yulida Nuraini Santoso, and others had a brief discussion about future institutional collaboration.

Logo and Mascot of 11th ASEAN Para Games (Foto: Jawapos)

Logo and Mascot of 11th ASEAN Para Games (Foto: Jawapos) Festival in Solo: Solo Batik Carnival (Foto: Instagram/ solobatikcarnival_official)

Festival in Solo: Solo Batik Carnival (Foto: Instagram/ solobatikcarnival_official)