Colonialism Beneath Protectionism: The Trade Disputes Between Indonesia and the European Union

Author: Daniel Situmeang Since the mid-20th century, many developing countries have been freed from the shackles of European colonial rule. Indonesia itself has been recognized as an independent state by […]

Unveiling Power Politics Behind Najib’s “Red-Carpet” Legal Treatment

Author: Aldi Haydar Mulia Photo by Bernd Dittrich on Unsplash In Malaysia, another twist to the tale of the convicted ex-Prime Minister, Najib Razak, has developed yet again. The Court […]

Forgotten: ASEAN’s Vision on Disaster Management

It was merely three months ago when Indonesians headed to the polls to elect their municipal leaders in the 2024 local elections. As many as 207 million eligible voters were […]

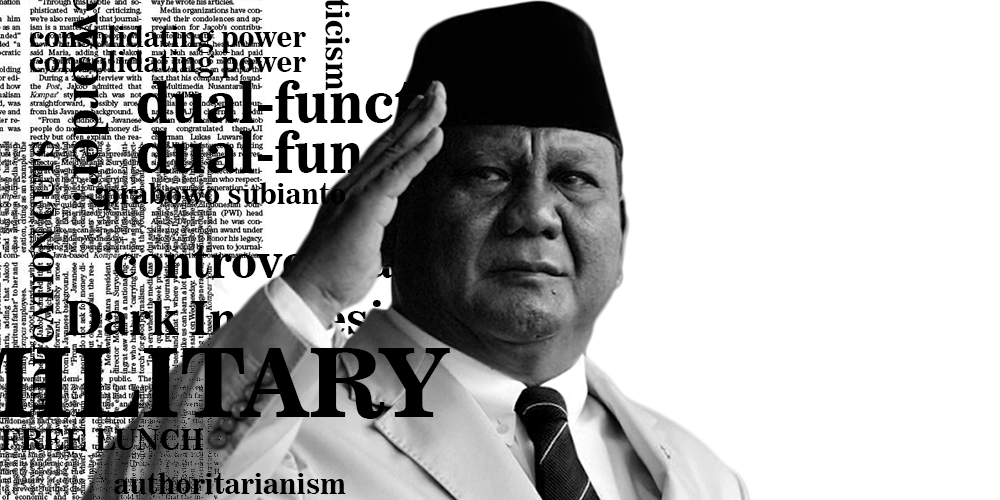

The Getaway Car Presidency: Prabowo, Power, and the Road to Nowhere

Drivin’ the getaway car We were flyin’, but we’d never get far Taylor Swift’s Getaway Car is a song about high-speed betrayals, thrilling escapes, and the eventual realization that running from one […]

ASEAN Studies Center – Japan Foundation Essay Competition

Background The Indo-Pacific region faces a complex and evolving landscape of strategic, economic, and security challenges. While Japan and ASEAN have maintained a longstanding partnership characterized by cooperation in areas […]

“Mapping the Critical Role of ACWC, CSOs, and Academia” and “ASEAN Post-2025 Vision Consultation”

A seminar titled “Mapping the Critical Role of ACWC, CSOs, and Academia” was held on November 1, 2024, at The Manohara Hotel Yogyakarta, Indonesia. This landmark event provided a significant […]

Policy Brief Competition

Top 3 Policy Briefs First Place – “Collaborating Youth Power for Child and Women Protection from Online Gambling Risks in ASEAN Countries”, by Muh. Rifki Ramadhan, Bagas Febi Cahyono, and […]

Public Lecture on “Navigating Contemporary Challenges: Indonesian Diplomacy in a Chanching Global Changes”

On September 12, 2024, the ASEAN Studies Center of Universitas Gadjah Mada and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia held a public lecture entitled “Navigating Contemporary […]

ASEAN Studies Center welcomed a visitation from Prof. Kimikazu Shigemasa from Kwansei Gakuin University, Japan

ASEAN Studies Center welcomed a visitation from Prof. Kimikazu Shigemasa from Kwansei Gakuin University, Japan on 11-12 September 2024. The discussions during the visit revolved around significant topics, including developments […]

Partnership Policy Review Kick Off – “Strengthening the ASEAN Charter: Review of Regional Mechanisms and Policy Recommendations”

In the last few decades, ASEAN has experienced a shift from a state-oriented policy to a people-oriented one. This has become momentum for strengthening the economic, political-security, and socio-cultural pillars. […]

ASEAN Spice: The Connecting Culture of Southeast Asians

Background Gastro-diplomacy, or culinary diplomacy, is a fascinating approach to international relations that leverages food to foster cultural exchange and build relationships between nations. In the context of the Association […]

ASC Commentaries | Charting the Course: ASEAN’s Quest for Clarity in the South China Sea

[av_headline_rotator before_rotating=’ASC Commentaries | Charting the Course: ASEAN’s Quest for Clarity in the South China Sea’ after_rotating=” margin=” margin_sync=’true’ av-desktop-margin=” av-desktop-margin_sync=’true’ av-medium-margin=” av-medium-margin_sync=’true’ av-small-margin=” av-small-margin_sync=’true’ av-mini-margin=” av-mini-margin_sync=’true’ align=’left’ custom_title=” size=” […]

RELIGION: BOON OR BANE FOR DEMOCRACY?

In December 2022, the Indonesian government passed a law that penalizes sex outside marriage. This is only one of the many changes in the criminal code that observers warn of […]

Redefining Commodities in International Trade: ASEAN Blue Carbon Initiative and Its Role in Navigating Climate Crisis in the Southeast Asia Region

Stepping further into the technological and industrial advancement age, the narration of sustainability in the international trade system has gained much attention from policymakers worldwide. Not only due to the […]

Korea-Indonesia Cooperation Forum in Commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of Diplomatic Relations

In order to celebrate 50 years of relations between South Korea and Indonesia. On November 30, 2023, the ASEAN Studies Center at Gadjah Mada University was invited to join the […]

NACT Country Coordinators Meeting and Annual Conference 2023

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP) are interconnected regions with significant potential for trade, infrastructure development, and economic growth. China introduced the […]

ASC UGM x Kemenko Polhukam Focus Group Discussion

Yogyakarta, 27 September 2023 – ASEAN Studies Center Gadjah Mada University (ASC UGM) x Coordinating Ministry for Political, Legal, and Security Affairs (Kemenko Polhukam) held a Focus Group Discussion (FGD). […]

Diplomatic Briefing and ASC Monograph 2023 Launch

Yogyakarta, 22 August 2023 – ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada (ASC UGM) held a Diplomatic Briefing event and the launch of the ASC Monograph 2023. The event had the […]

Open House ASC UGM: ASEAN Day!

On August 8, 2023, the ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada held an Open House in celebration of the 56th anniversary of ASEAN Day, in the BC building room no. […]

ASEAN Chairmanship 2023: Indonesia’s Tendency to Solve the South China Sea Territorial Disputes

On 13 November 2022, the handover of ASEAN chairmanship from Cambodia to Indonesia was held at the ASEAN summit. Adopted the “ASEAN Matters: Epicentrum of Growth” theme, Indonesia is responsible […]

Embracing ASEAN Economic Community 2025: Unlocking Prospects and Overcoming Obstacles in Indonesia

Imagine businesses of all sizes, effortlessly trading goods and services across ASEAN borders, tapping into diverse markets, and seizing growth opportunities. Picture investors eagerly exploring investment prospects in ASEAN, fueling […]

Institutional Visitation by Prince of Songkla University – FISIPOL and PSU Future Collaboration

Yogyakarta, Friday, March 3, 2023 FISIPOL together with the ASEAN Studies Center UGM welcomed the institution from the Prince of Songkla University (PSU), Thailand. This meeting was held in Dean’s […]

Public Seminar – Indonesia’s Agenda in ASEAN Chairmanship 2023: Opportunities and Challenges

Indonesia’s Chairmanship role in the midst of the dynamics of global issues that are always challenging at this time is driven by strong initiatives to build a regional region that […]

ASEAN’s Pathway to Sustainability Through Green Recovery Post-Pandemic Covid-19: Challenge and Opportunity

Written by Wahyu Candra Dewi Striking in 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic has significantly brought disruption to people’s livelihoods worldwide. Upon its initial announcement in March, the pandemic extended from a […]

What’s Missing in the AHRD?: Synergizing with Civil Society Towards Better Human Rights Regime in ASEAN

Written by Gerald John C. Guillermo Civil society has long been a bastion of service and advocacy—contributing to the development and uplifting of lives, particularly in marginalized and underprivileged sectors […]

ASC UGM at FISIPOL UGM Research Days 2022

Last week on FISIPOL Research Days 2022, our research on Halal Tourism has been presented by Dra. Siti Daulah Khoiriati as the lead researcher of this research project. In this […]

ASEAN’s Human Rights Promises and Pitfalls: Is the ASEAN Effective in Advancing its Human Rights Agenda?

Written by Arvhie Santos Background When the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) first recognized the concept of human rights in the ASEAN Charter promulgated in 2007, which led to […]

ASEAN at a Crossroads: An Autocratic Turn in the Region

According to Democracy Report 2022, published by V-Dem Institute, Southeast Asian countries were reported to experience either democratic stagnation or regression, indicating a shift towards a more autocratic region. Although […]

The Challenge of ASEAN Institutionalism in Outer Space

Written by: Ade Meirizal & Dinda Julia Putri A lot of people are blurry to consider space. Space activities are more complex. Not only for telecommunication, banking, and GPS utility, […]

AUKUS Impact for Achieving ASEAN Vision 2025

Written by: Hastian Akbar Stiarso & Rayhan Fasya Firdausi The newly formed trilateral security partnership between Australia, the UK, and the United States (AUKUS) on 16 September 2022 is a […]

ASEAN Back in the Indo-Pacific Saddle

Written by: Seonyoung Yang Indo-Pacific has been one of the most spoken buzzwords regionally and globally. Discourses for conceptualizing Indo-Pacific are still in progress. The rift caused by exacerbated US-China rivalry, […]

ASC Commentaries | Cross-Border Digital Payment Integration: What Will We Achieve?

[av_heading heading=’ASC Commentaries | Cross Border Digital Payment Integration: What Will We Achieve?’ tag=’h3′ style=” subheading_active=” show_icon=” icon=’ue800′ font=’entypo-fontello’ size=” av-medium-font-size-title=” av-small-font-size-title=” av-mini-font-size-title=” subheading_size=” av-medium-font-size=” av-small-font-size=” av-mini-font-size=” icon_size=” av-medium-font-size-1=” av-small-font-size-1=” […]

Ambassadorial Lecture on ASEAN-Egypt Outlook: Challenges and Future Prospects

On Monday, 29th November 2021, the ASEAN Studies Center held an Ambassadorial Lecture on ASEAN-Egypt Outlook: Challenges and Future Prospects. The lecture takes place online by streaming on ASEAN Studies […]

Time to Prepare Rowing between Two Great Islands Again

Since the mid of September 2021, there has always been news and columns about AUKUS in the mass media headlines. AUKUS, the trilateral military cooperation between Australia, the UK, and […]

Bincang ASEAN ReaLISM #3 | Reading, Learning, and Invesigating Southeast Asia through Movies

On Friday, 26th November 2021, ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada held a Bincang ASEAN – ReaLISM #3 “Reading, Learning, and Investigating Southeast Asia through Movies.” In this Bincang ASEAN, ASC UGM […]

Bincang ASEAN – ReaLISM #1 | Reading, Learning, and Investigating Southeast Asia through Movies

On Wednesday, 29th September 2021, ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada held a Bincang ASEAN – ReaLISM #1 “Reading, Learning, and Investigating Southeast Asia through Movies.” In this Bincang ASEAN, […]

Focus Group Discussion ASEAN Institute for Peace and Reconciliation: “”The Role of ICT as a Tool in Mitigating Conflict and Fostering Peace”

Monday, 25 January 2021 ASEAN Studies Center UGM attended Focus Group Discussion (FGD) organized by ASEAN Institute for Peace and Reconciliation with the main theme “The Role of ICT […]

Bincang ASEAN on ASC Monograph 2020 “Small States, Strong Societies: Essays on Covid-19 Responses in Southeast Asia”

Tuesday, 19th January 2021 ASEAN Studies Center UGM held the webinar series in Bincang ASEAN on ASC Monograph 2020, entitled “Small States, Strong Societies: Essays on Covid-19 Responses in Southeast […]

Theorizing a College of Southeast Asia

By Truston Yu (Photo: Vindur, Polish Wikipedia) For seven decades, the College of Europe has produced distinguished alumni members who had gone on to take up important posts in the […]

A Switzerland Model for Timor-Leste? Prospects of Differentiated Integration in ASEAN

By Truston Yu (Photo: VOA) Nearly two decades have passed since Timor-Leste became Southeast Asia’s youngest country, their quest for membership in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) remains […]

5 Months Left for Southeast Asia to Build the Case in UNSC

By Truston Yu (Photo: White House, Pete Souza) On 17 June, the United Nations General Assembly elected the new class of non-permanent members to the United Nations Security Council. India […]

ASEAN Cultural Exchange in the Era of Interconnectedness – Examining the 3 Campus Model

By Truston Yu (Photo: Culture 360 Asia-Europe Foundation) In my very first lecture on Southeast Asian politics, I learned about the creation of an institutionalized Southeast Asian Studies discipline in […]

What Southeast Asian Studies Could Learn from Japan

By Truston Yu (Picture: CSEAS Kyoto University) The Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS) at Kyoto University could be seen as the pinnacle of Southeast Asian Studies in Japanese scholarship. […]

Southeast Asian Studies and ASEAN Studies: What’s the Difference?

By Truston Yu (Picture: Businesswest) Ever since I began my research on Southeast Asia, there has been a lingering question that intrigued me: what is the difference between Southeast Asian […]

A Provincial Level Approach to Studying China-Southeast Asia Relations

By Truston Yu (Picture: Wikimedia) With the implementation of projects under the Belt and Road umbrella, China is becoming increasingly relevant to Southeast Asia. While China’s relative influence might be […]

How Taiwan Could Capitalize on its New Southbound Policy

By Truston Yu (Picture: Wikimedia) 20 May 2020 marked the inauguration ceremony of Taiwan’s reelected President Tsai Ing-wen, signaling a continuation of her New Southbound Policy (NSP), which engages eighteen […]

Press Release – “Diplomatic Briefing on the ACWC 10th Year Commemoration – Solidifying the Role of Think Tanks and CSOs in the Advocacy to Strengthen the ASEAN Commission of Women and Children (ACWC)”

In continuation of the commemoration of the 10th anniversary of the ASEAN Commission on the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Women and Children (ACWC), the ASEAN Studies Center […]

Press Release Public Lecture: “The Politics of Leadership Succession: A Comparative Perspective across Democratic and Non-democratic Regimes”

Yogyakarta, 20 August 2019 On Tuesday 20th August 2019, ASEAN Studies Center UGM welcomed the new semester with a public lecture by Professor Ludger Helms from the University if Innsbruck, […]

CREATING A DRUG-FREE ASEAN: HOW FAR HAVE WE COME?

By Jonathan Evert Rayon Based on the World Drug Report in 2018, 31 million people worldwide suffered from drug use disorders resulting in millions enduring health risks such as hepatitis […]

OUT OF JAKARTA: RELOCATION OF INDONESIA’S CAPITAL AND ITS IMPLICATIONS

By Truston YU Image: Merdeka Palace Changing Guard by Gunawan Kartapranata President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo recently announced plans to relocate Indonesia’s capital city to outside Java. Following Myanmar’s move from […]

ASEAN, EU collaboration needed to resolve palm oil dispute

Image: Palm oil mill in Sabah, Malaysia © CEphoto, Uwe Aranas The failure to upgrade ties between the EU and ASEAN to a new strategic dialogue partnership at the 22nd ASEAN-EU […]

Research on ASEAN Aviation Industry

[av_section min_height=’50’ min_height_px=’500px’ padding=’large’ shadow=’no-border-styling’ bottom_border=’no-border-styling’ bottom_border_diagonal_color=’#333333′ bottom_border_diagonal_direction=” bottom_border_style=” custom_margin=’0px’ custom_margin_sync=’true’ custom_arrow_bg=” id=” color=’main_color’ background=’bg_color’ custom_bg=” background_gradient_color1=” background_gradient_color2=” background_gradient_direction=’vertical’ src=’http://web05.opencloud.dssdi.ugm.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/sites/741/2019/03/Profile.jpg’ attachment=’3390′ attachment_size=’full’ attach=’parallax’ position=’center left’ repeat=’no-repeat’ video=” video_ratio=’16:9′ overlay_opacity=’0.5′ overlay_color=” […]

Indonesia Refugee Policy is on Right Track

January 2019 marks two years of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s 2016 presidential decree on handling foreign refugees. The Presidential Decree no. 125/2016 on the Treatment of Refugees from Overseas, […]

Quo Vadis: Thailand’s Taking the Chair of ASEAN, Sailing in the Troubled Waters

After one year, Singapore has led the Association to progress in ASEAN’s three pillars, the next torch of the Association is now in Thailand’s grip. Faced with relentless fights against […]

The Challenges of Indonesia’s Palm Oil Industry: An Overview

The global debate on the sustainability and legitimacy of palm oil production is one that continues to evolve and define the industry. As Indonesia and Malaysia are the two major […]

ASEAN on Disaster Management: Earthquake and Tsunami in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia

7,7 SR Earthquake and 1.5-meter-high tsunami hit Central Sulawesi, Indonesia on September 28th, 2018. The natural disaster caused various physical destructions, and fatalities; the death toll reached 1,948, and thousands […]

Press Release Bincang ASEAN “What Can ASEAN Do For Rohingya?”

Yogyakarta, Friday, November 24th, 2018 The series of Bincang ASEAN was concluded with a very problematic discussion over the humanitarian crisis situation in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. This Bincang ASEAN was […]

Press Release Bincang ASEAN “Gender in ASEAN”

Yogyakarta, Friday, November 9th, 2018 The ASEAN Studies Center UGM and ASEAN Studies Center UMY held its first collaborated Bincang ASEAN entitled “Gender in ASEAN” at Amphitheater E6 K.H Ibrahim […]

Modern Slavery: A Fight, Not Yet Won

The term slavery may sound a little bit old, but in fact, slavery still exists in this era with a new term: modern slavery. The term modern slavery is an […]

Press Release Bincang ASEAN “Transnational Activism for Migrant Workers in Asia: The Case of Indonesia and the Philippines”

Yogyakarta, October 26th 2018 Yogyakarta – On Friday, October 26, 2018, ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada held the fourth edition of Bincang ASEAN 2018. Approximately 50 students and practitioners […]

Press Release Bincang ASEAN “Delegate Sharing Session: Model ASEAN Meeting Experiences”

Yogyakarta, Friday, October 12, 2018 ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada held its very first collaborated Bincang ASEAN featuring the Department of International Relations, Universitas Islam Indonesia. In order to […]

Press Release BINCANG ASEAN “Mapping the Source of Indonesia’s Refugee Obligations: Does it Exist?”

Yogyakarta, 6th September 2018 ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada held the second meeting of Bincang ASEAN in Thursday (6/9), with Dio Herdiawan Tobing S.IP, LLM, former researcher at […]

Bincang ASEAN: Mapping the Source of Indonesia’s Refugee Obligations: Does it Exist?

[ASC EVENT] Bincang ASEAN With more than 13,000 asylum-seekers and refugees currently hosted in Indonesia, the country is regarded as one of the main refugee transit countries in Southeast Asia […]

Panmunjom Agreement: The Role of ASEAN behind the Pacified Peninsula

Rafyoga Irsadanar A new stage of peacemaking had progressed in the Korean Peninsula as Kim Jong Un and Moon Jae-in declared that there will be no more war in the […]

Seminar on Enhancement of Cooperation between Eastern Part of Indonesia and Southern Part of the Philippines

Seminar on Enhancement of Cooperation between Eastern Part of Indonesia and Southern Part of the Philippines 23 August 2018 | 8.30 – 16.45 | R. Seminar Timur, Fisipol UGM REGISTRATION […]

Rethinking Strategies and Opportunities for ASEAN in 40 Years of Establishment of ASEAN-EU Dialogue Relations

Chitito Audithio Syafitri The year 2017 marks the 40th commemoration of ASEAN – EU Dialogue Relations, which brought together the two countries to adopt a Joint Statement on the 40th […]

ASEAN AND THE UN PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS – International Day of UN Peacekeepers

Kevin Iskandar Putra May 29th 2018 remarks the 70th Years of Service and Sacrifice of the UN Peacekeepers. Through the General Assembly Resolution 57/129 on the report of the Special […]

Press Release BINCANG ASEAN “Democratization in Southeast Asia: The Case of Indonesia, Philippines and Thailand”

Bincang ASEAN Monday, 14 May 2018 Yogyakarta – Recently, the ASEAN Studies Center UGM held its first Bincang ASEAN in 2018 entitled “The Democratization in Southeast Asia: The Case of […]

Indonesia should partner with NGOs to protect unaccompanied child refugees

Among more than 3,700 child refugees in Indonesia, close to 500 are unaccompanied minors. Many have no access to formal education and health care. They have to go through the […]

Internship Program

ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gajah Mada membuka kesempatan magang untuk mahasiswa dari seluruh jurusan di universitas di Yogyakarta yang akan berkesempatan untuk terlibat dalam riset serta program akademik yang diselenggarakan […]

Indonesian Foreign Policy under Three Years of Jokowi’s Administration

Siti Widyastuti Noor October 2017, marked the third year of administration for Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi’ Widodo. In the beginning of his administration, Jokowi announced the nine prioritized agendas as […]

The ASEAN Enhanced Disputes Settlement Mechanism (EDSM): Functional for Economic Growth or Protecting National Sovereignty?

Suraj Shah As the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) seeks to deepen regional economic integration, the Enhanced Dispute Settlement Mechanism must avoid politicisation to optimise successful integration and economic development in […]

Day 3: UGM-RUG International Working Conference on Regional and National Approaches Toward Sustainable Development Goals in Southeast Asia and ASEAN

The third day of UGM-RUG International Working Conference on Regional and National Approaches toward Sustainable Development Goals in Southeast Asia held on October 5th 2017. With only three session of […]

Day 2: UGM-RUG International Working Conference on Regional and National Approaches Toward Sustainable Development Goals in Southeast Asia and ASEAN

The second day of UGM-RUG international working conference on October 4th 2017 was opened by Prof. Dr. Ronald Holzhacker draft paper presentation the relation of multi-level governance and the sustainable […]

UGM-RUG International Working Conference on Regional and National Approaches Toward Sustainable Development Goals in Southeast Asia and ASEAN Day 1

ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada and the Groningen Research Centre for Southeast Asia and ASEAN, University of Groningen, organized international working conference on regional and national approaches toward sustainable […]

Indonesia Drags Its Feet on ASEAN Haze Treaty

Dio Herdiawan Tobing, Universitas Gadjah Mada In May, I went with my research team to Palangka Raya, Central Kalimantan, one of Indonesia’s hotspots of land and forest fires. We wanted […]

To protect migrant workers, Indonesia should engage multiple stakeholders

ASEAN Studies Center UGM held the seventh Bincang ASEAN which discusses some problems that Indonesian migrant workers face in several countries. This discussion is triggered by the recent problems regarding […]

ASEAN Studies Center Introduced at Groningen Fall Conference on Challenges of Governance in Southeast Asia and ASEAN

On Tuesday (12/9), M. Prayoga Permana and Dio Herdiawan Tobing, introduced ASEAN Studies Center (ASC) Universitas Gadjah Mada and its the newly established cooperation with Groningen Research Centre on Southeast […]

Indonesia’s refugee policy – not ideal, but a step in the right direction

Dio Herdiawan Tobing The Indonesian government needs to expand a presidential decree to protect refugees, by turning it into law. The definition the decree uses should also be broadened because […]

ASEAN After 50: Social Integration and the Challenges of New Geopolitics

Ahmad Rizky M. Umar and Karina Larasati B. Riyanto What should ASEAN do in the next 50 years? For ASEAN, its survival for the last 50 years is a […]

ASEAN After 50: ASEAN and Good Governance

Pinto Buana Putra ASEAN is a regional organization that is build to accelerate cooperation between member states in regional level. Within ASEAN there is no uniform political quality that would […]

ASEAN After 50: Mainstreaming Paradiplomacy in ASEAN

Ario Bimo Utomo During the last few decades, sub-state entities have been rising to prominence due to the increasing level of globalization. Anthony Giddens argues that this phenomenon is caused […]

ASEAN After 50: The Language of Gender Discrimination in Southeast Asia

Farieda Ilhami Zulaikha Why talk when you are a shoulder or a vault Why talk when you are helmeted with numbers Fists have many forms; a fist knows what it […]

ASEAN After 50: Reflecting ASEAN as Collective Identity

Rifki Maulana Iqbal Taufik The 50th anniversary of ASEAN is the right moment to evaluate every achievement and the projections for the future. An evaluation is not limited only to […]

ASEAN After 50: Climate Justice and Smallholder farmers

Ibnu Budiman The combination of climate change mitigation and adaptation is essential for millions of smallholder farmers in ASEAN. However, does it consider farmers’ rights and development to achieve a […]

ASEAN After 50: Is the ‘ASEAN Way’ still relevant?

Dio Herdiawan Tobing Unlike other regional or international organizations, ASEAN possesses its own model of diplomatic engagement: the ASEAN Way. For so many years, the ASEAN Way has always been […]

ASEAN After 50: Rethinking ASEAN-China Cultural Cooperation

Dr. Gabriel Lele ASEAN-China cooperation has stepped towards a new phase in the recent decade. As ASEAN is celebrating its 50th anniversary, it is important to rethink the cooperation in […]

ASEAN After 50: Studying the Lands Below the Winds

Dendy Raditya A. On August 8th this year, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) will celebrate its 50th anniversary. This is the right time to reflecting on what had […]

ASEAN After 50: Defending Human Rights in ASEAN

Jakkrit Chuamuangphan As 2017, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) marks 50 years since first founded in 1967. To date, ASEAN has shown a huge success in realizing the regional […]

ASEAN After 50: Escaping the Middle Income Trap

Suraj Shah Several ASEAN member states such as Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam and Indonesia have sustained impressive growth rates in recent decades. Whilst this is a good news for […]

ASEAN After 50: Why Political and Economic Integration are Not Sufficient

Ahmad Rizky Mardhatillah Umar ASEAN is now 50 years old. Originally established only as a platform for interstate dialogue, ASEAN has progressed through the ‘long and winding road’ to become […]

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons: Historic Progress, Yet Not a Complete End to the Struggle

122 members of the United Nations, including Indonesia, voted in favor for the adoption of an international treaty eliminating the use of nuclear weapons, at the UN Conference to Negotiate […]

AYIEP Participants Learn from Asian Start-Ups

After joining International Seminar on ASEAN 50th Anniversary at the 1st day, the ASEAN Youth Initiative Empowerment Program (AYIEP) continues by presenting two public lectures from young, creative digital entrepreneurs. […]

Ambassador Ong Keng Yong: Digital Transformation is the Future of ASEAN Integration

ASEAN’s 50th anniversary should be addressed by nurturing digital integration, says H.E. Ambassador Ong Keng Yong, former ASEAN Secretary-General in FISIPOL UGM (27/7). Speaking as a Keynote Speaker at an […]

Digitalizing ASEAN (2): Three Key Pillars

In the second of two-series article, we introduce ASEAN Youth Initiative Empowerment Programme, a one-week program for ASEAN Youth organized by ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada. The theme of […]

Digitalizing ASEAN (1): What It is and Why It is Important

In this first series of article, we introduce ASEAN Youth Initiative Empowerment Programme, a one-week program for ASEAN Youth organized by ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada. The theme of […]

Bincang ASEAN Discusses EU and ASEAN Model of Integration

ASEAN Studies Center UGM held the sixth meeting of Bincang ASEAN in Friday (19/5), which invited Prof. Janos Vandor (Professor at Budapest Business School) and Suraj Shah (Graduate Student at […]

ASC Discusses Global Discourses on Rohingya

ASEAN Studies Center UGM held the fifth meeting of Bincang ASEAN in Friday (12/5), which invitedHadza Min Fadhli Robbi, S.I.P. (alumnus of the Department of International Relations who is currently […]

ASEAN Economic Community: In Search of a Single Production Base

A key motivation behind the pursuit of a comprehensive ASEAN Economic Community is to establish a single production base. By doing so, ASEAN member states hope to increase their competitiveness, […]

Marawi’s Crisis Requires ASEAN’s Centrality, Not External Intervention

Since the past two weeks, Southeast Asia has been putting a serious concern to its security and stability caused by the state of crisis in Marawi and Mindanao. Isnilon Hapilon, […]

ASC Welcomed Professor Anders Uhlin from Lund University

On Monday (6/5), ASEAN Studies Center received a visit of Professor Anders Uhlin from Lund University, Sweden. He visited our institution in conjunction with his agenda to be a speaker […]

ASEAN Summit 2017: A Conclusion to South China Sea?

In April this year, the ASEAN Summit kicked off at the heart of the Philippines – Metro Manila. With the theme entitled “Partnering for Change, Engaging the World”, this summit […]

Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI) and the New Politics of Regionalism in Southeast Asia

China officially launched the Belt and Road Initiatives on May 2017. Attended by 29 partner countries (with the absence of some prominent neighbours such as India), the launching of the […]

UAE-ASEAN Relations: Beyond “Emirates’ Diplomacy”?

In the past several years, there is an increasing tendency among the countries of the Gulf to direct their foreign policies towards the growing economies of Asia. Despite relatively unreported, […]

‘Brexit’, the European Union, and the ‘Communication Deficit’: A Lesson for ASEAN

‘Brexit’ has created shockwaves through the European Union and called into question whether regional integration is sustainable, and ASEAN is watching developments closely. A key issue that ASEAN must learn […]

Has ASEAN Moved Away from ZOPFAN?

From April 26-29, Manila hosted the 30th ASEAN Summit. The summit is expected to make progress on the current geopolitical crisis which affects the Southeast Asian region. Among the rests, […]

Why ASEAN Needs to Regulate Land and Water Grabbing Issues

Political stability and food security are inter-related both at national and regional level. The distortion of political instability would eventually affect food availability and distribution. On the one hand, food […]

Developing Halal Tourism within IMT-GT Sub-regional Cooperation

Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand held the 10th Indonesia-Malaysia-Thailand Growth Triangle in Manila, Philippines. Represented by the presence of Indonesian President Joko Widodo, Malaysian Prime Minister Dato’ Seri Najib Razak, and […]

Book Review: ASEAN in 2017, Regional Integration in an Age of Uncertainty

Studying ASEAN as a region, its policy, relations among member countries, and geopolitical situations has attracted many scholars to inscribe their ideas and analysis. ASEAN in 2017: Regional Integration in […]

Bincang ASEAN: ASEAN in 2017, Regional Integration in an Age of Uncertainty

Earlier this year, four researchers from ASEAN Studies Center, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Gadjah Mada, namely Ahmad Rizky M. Umar, Dedi Dinarto, Dio Herdiawan Tobing, and Shane […]

Capital Drugs Law in Southeast Asia: A Homicide against Humanity

Southeast Asia is one of the world’s largest markets for synthetic drugs and capital drugs law is highly practiced by retentionist states in the region. ASEAN largest member states: Indonesia, […]

Why Southeast Asia is Prone to North Korea’s Crisis

Regional instability remains one of the serious concerns for Southeast Asian countries. ASEAN itself is facing unresolved conflicts and disputes that push the regional institution into stalemate position. Rohingya Refugees’ […]

New Visiting Research Fellow at ASEAN Studies Center

We welcome our New Visiting Fellow, Mr Suraj Shah from International Development Institute, King’s College London. Mr Shah will be working on his Dissertation research, which will discuss “The Political Economy of […]

ASEAN at 50: Has the Philippines Enhanced the Power of ASEAN’s People?

ASEAN agreed to put its concern on the importance of its people through the pillar of ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC). Among the three pillars, ASCC is conceivably the one given […]

Is Single-sex Education Promoting Education Equality?

Seeking to promote the education equality for boys and girls, ‘Single-sex Education’ has become a growing trend. Sex segregated education, which separates boys and girls, or commonly known as Single-sex […]

ASC Researchers Partake in Roundtable Discussion with U.S. Embassy and National War College

Today (07/4), two ASEAN Studies Center’s Researchers, Dedi Dinarto and Dio Herdiawan Tobing took part in Roundtable discussion with delegates from the U.S. Embassy and National War College. The […]

Socialising Human Rights in ASEAN

U Ko Ni, a legal advisor of National League for Democracy (NLD), was shot in Rangoon Airport on February. He was returning from an official visit to Indonesia addressing […]

ASC Researcher Joins Worldwide Debate on IORA and ASEAN

Our Researcher Dedi Dinarto engaged in a debate on whether Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) will undermine ASEAN centrality in Indonesia’s foreign policy. Earlier this month, Dedi published an article […]

ASEAN Studies Center Holds Research Workshop

On Friday (31/3), ASEAN Studies Center (ASC) Faculty of Social and Political Sciences Universitas Gadjah Mada had successfully organized our first research workshop at Jogjakarta Plaza Hotel. The workshop aims […]

New ASC Book: “ASEAN In 2017: Regional Integration in an Age Of Uncertainty”

ASEAN Studies Center UGM is pleased to launch a new book that covers a regional outlook in 2017. Co-authored by four ASEAN Studies Center’s researchers, this book highlights three key […]

Pengumuman Seleksi Wawancara AYIEP 2017

Yth. Kepada seluruh peserta seleksi Panitia AYIEP 2017, Setelah melalui proses seleksi yang panjang dan dengan kompetisi yang tinggi, kami mengumumkan hasil seleksi wawancara panitia ASEAN Youth Initiative Empowerment Program […]

Modelling International Lawmaking in ASEAN

ASEAN and its model of international law has always being questioned by many international lawyers for its informal nature of law-making processes in concluding agreements among member states. For […]

Pengumuman Jadwal Wawancara AYIEP 2017

Berikut adalah peserta yang lolos seleksi berkas beserta jadwal wawancara yang ditentukan. Wawancara akan diadakan di kantor ASEAN Studies Center Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik, Gedung BC ruang 209. […]

Bincang ASEAN Discusses “Politics in the Boardroom”

ASEAN Studies Center UGM held the second meeting of Bincang ASEAN in Friday (17/3), which invited Indri Dwi Apriliyanti (Lecturer at Department of Public Policy and Management, FISIPOL UGM and […]

Why Indonesia Needs to Reform Maritime Security Governance

President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) seems not to show any significant progress in the aspect of maritime security governance. The reason lies under the ignorance towards the existence and role […]

Is Indonesia Choosing the Indian Ocean Rim Association Over ASEAN?

Indonesia’s substantial involvement in IORA signifies a stage of crisis for ASEAN. From March 5 to 7, Jakarta played host to the leader’s summit of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), […]

ASEAN Economic Community Today: From Neo-liberalism to New Structuralism?

In 2010, the World Bank published a book that shed light on a new framework for world development: New Structural Economics. Authored by the Bank’s Chief Economist Justin Yifu Lin, […]

Migration-Development Nexus: The Launching of Bincang ASEAN in UGM

ASEAN Studies Center UGM has launched Bincang ASEAN, a regular event that provides critical discussions over recent development in ASEAN. The first discussion was held in Friday (3/3) in BC […]

ASEAN Studies Center UGM Leads Review of ASEAN Charter

ASEAN Studies Center UGM, in collaboration with the Coordinating Ministry of Politics, Law and Security arranges a Focused Group Discussion to the discuss the review of ASEAN charter, which will […]

Pengumuman Hasil Seleksi Wawancara ASEAN Studies Center 2017

Yth. Kepada seluruh peserta internship ASC 2017, Setelah melalui proses seleksi yang panjang dan dengan kompetisi yang tinggi, kami mengumumkan hasil lolos seleksi wawancara Program Internship ASEAN Studies Center […]

Pengumuman Wawancara Internship Program 2017

Berikut adalah peserta yang lolos seleksi berkas beserta jadwal wawancara yang ditentukan. Wawancara akan diadakan di kantor ASEAN Studies Center Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik, Gedung BC ruang 209. […]

ASEAN Countries Should Find a Solution to End the Persecution of Rohingya

Ahmad Rizky M. Umar – Research Fellow at the ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada ASEAN’s non-intervention is aggravating the plight of ethnic Rohingya Muslims suffering widespread abuse by the Burmese military […]

The Future of ASEAN-Russian Relations

Shane Preuss, Research Intern at the ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada ASEAN’s strength is demonstrated by its ‘convening power’ and its ability to attract the courtship of the world’s […]

The Future of ASEAN-Australian Relations

Shane Preuss, Research Intern at ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada 2016 was a significant year for Australian ASEAN relations. The First ASEAN-Australia Biennial Summit was held on 7 September 2016 […]

ASEAN Toward Global Market Integration: Enhanced Connectivity & External Relationship

Arrizka Permata Faida Best 10 Author of Call for Essay: ASEAN Community Post 2015 The establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in 2015 is a major milestone in the […]

Indonesia Needs to Step up Its Fight Against Maritime Piracy

Dedi Dinarto – Researcher at ASEAN Studies Center UGM Indonesia’s maritime sector gained a boost when on December 21, Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs Luhut Binsar Panjaitan agreed to cooperate with Japan, establishing […]

What ‘Brexit’ and ‘Trump’s Triumph’ Warn Us About ASEAN Community

Shane Preuss, Research Intern at ASEAN Studies Center, Gadjah Mada University One year after the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community, it is important to ask what relevance the […]

ASEAN Political-Security Community: The Prospect of South China Sea

Muhammad Ammar Hidayahtulloh Best 10 Author of Call for Essay: ASEAN Community Post 2015 ASEAN is located strategically at the crossroads of the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, and […]

Behind EU-ASEAN Free Trade Agreements: Do Norms Matter?

Shane Preuss, Research Intern at ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada The EU is currently attempting to pursue both normative political interests and economic interests in the ASEAN. I argue that […]

Where is ASEAN in Indonesia’s Foreign Policy? Jokowi after Two Years

Ahmad Rizky M. Umar Research Associate at ASEAN Studies Center UGM Under President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, Indonesia appears less oriented toward the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Earlier in […]

The Role of International Organization in Managing Global Refugee Crisis

Thursday, 24 September 2016 Gedung BD Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik, Universitas Gadjah Mada This public lecture aims to discuss the problem of refugee issues, which has been […]

A Single Monetary Regime in ASEAN: Panacea or False Hope

Muhammad Rasyid Ridho[1] & Wening Setyanti[2] 3rd Winner of Call for Essay: ASEAN Community Post 2015 Basically, there are four pillars under ASEAN economic integration: (1) a single market and production […]

Drawing ASEAN Limits and Strengths in Tackling Terrorism: Study Case of Abu Sayyaf Group

Novita Putri Rudiany-Kholifatus Saadah 1st Winner of Call for Essay: “ASEAN Community post 2015” ASEAN actually had discussed terrorism issue before 9/11 happened, since the summit in 1997 and […]

Public Lecture: Haze Indonesia and Beyond

Trump and the Death of ‘Pivot to Asia’ Doctrine

Bara E. Brahmantika, Guest Contributor The result of 2016 US election has paved the way for Donald Trump to be the 45th president of United States, and many people are […]

What Comes after ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) 2015: A Threat from China’s Economic Downfall

Niki Wahyu Sayekti, 2nd Winner of Call for Essay: “ASEAN Community Post 2015” ASEAN governments have spent decades crafting their reliance on the Chinese economy, with a strategic relationship shaped […]

Donald Trump and the Global Politics of “Strongman Leaders”

Habibah Hermanadi, Research assistant of ASEAN Studies Center UGM Donald Trump has been elected as the 45th President of the United States. As predicted, the result triggered massive reaction […]

What does “Trump’s Triumph” Mean for ASEAN?

Dedi Dinarto, Researcher at ASEAN Studies Center UGM The triumph of Donald Trump for the presidential election in the United States of America has brought about a shock for world […]

Winners of “Call for Essay: ASEAN Community Post 2015”

It’s been three weeks since we, ASEAN Studies Center team, announcing a competition on Call of Essay: “ASEAN Community Post 2015”. We are glad to have so many participant which […]

Does Indonesia Need a “Post-ASEAN” Regional Order?

Ahmad Rizky M. Umar In his recent article in The Jakarta Post (18/5), Rizal Sukma (now Indonesian Ambassador to the United Kingdom) embraced an interesting argument: it is time to […]

Public Lecture: Indonesia’s Foreign Policy during Jokowi: With or Without ASEAN?

Under President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, Indonesia appears less oriented toward the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Earlier in 2014, Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi embraced several new ideas on how […]

The Groundbreaking Ceremony of Cooperation between ASEAN Studies Center UGM and Groningen Research Centre for SEA and ASEAN, University Of Groningen

ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada (ASC UGM) merupakan satu dari sekian pusat studi ASEAN yang ada di Indonesia dengan inisiatif kerja sama dan produktivitas penelitian yang paling intensif. Sebagai […]

ASEAN Countries Military Strength Infographic

Call for Essay: ASEAN Community Post 2015

ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada mengadakan Kompetisi Esai dengan tema “ASEAN Community Post 2015” dengan ketentuan sebagai berikut: Subtema Socio-Cultural Pillar Economic Pillar Political and Security Pillar Ketentuan […]

The Way of ASEAN Non-Confrontation: Backdoor Diplomacy or The Inability to Conduct Diplomacy in Public Spaces

Dio Herdiawan Tobing, Research Intern at ASEAN Studies Center UGM In the past few days, Indonesia’s first Right of Reply in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) has attracted […]

In the Thick of Fear and Idea: Wither ASEAN Centrality?

Dedi Dinarto Long before the discourse on the future of ASEAN centrality, S. Rajaratnam and Thanat Khoman have put their respective ideas on the ontological part of ASEAN, meaning […]

ASEAN fights against trans-border crime

This article was published on 7 September 2016 in Jakarta Post Dedi Dinarto – Research Assistant at ASEAN Studies Center UGM Given the rising concerns over transnational organized crime in […]

Southeast Asia: Refugee Crisis and the Customary Law of Non-Refoulement

Dio Tobing – Intern at ASEAN Studies Center, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Gadjah Mada If the European Union is still dealing with mass influx of forced […]

2016 Student Working Paper: Call for Paper

ASEAN Studies Center (ASC) FISIPOL Universitas Gadjah Mada in collaboration with INKA KOMAHI, encourage you IR Students across Indonesia to contribute your paper for Student Working Paper ASC UGM 2016. […]

Glimpse of Hope: Student-led Protest in Malaysia

Dedi Dinarto – Research Assistant at ASEAN Studies Center, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Gadjah Mada Encouraging students to actively participating in protest movement remains arduous. The busy […]

The 49th ASEAN: Who Does What and How?

Dedi Dinarto – Research Assistant at ASEAN Studies Center, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Gadjah Mada Indonesian scholar Shofwan Al Banna Choiruzzad through his prominent book titled ‘ASEAN […]

From a Security Regime into a Security Community: Is it Time?

Habibah H. Hermanadi – Research Intern at ASEAN Studies Center UGM 2016 begun with yet another terrorist attack to one of the ASEAN member states, Indonesia, the attempt of suicide […]

Sea as Political Space under ASEAN’s Flag

The obscurity of ASEAN facing the South China Sea issue after the victory of the Philippines against China in the tribunal ruling showed the fragmented ASEAN. Various views criticized potential […]

Seeking a Common Ground

By Habibah H. Hermanadi, Research Intern at ASEAN Studies Center UGM At the end of the 2016 ASEAN regional summit all member states are looking forward to the joint declaration […]

1st ASEAN Youth Initiative Empowerment Program 2016

ASEAN Studies Center, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Gadjah Mada, is proud to launch our 1st ASEAN Youth Initiative Empowerment Program 2016 that aims to increase the awareness […]

After Tsunami: ASEAN Reborn?

Mohammad Hazyar Arumbinang, Intern staff ASEAN Studies Center UGM. A powerful Indian Ocean earthquake was constructed on December 26, 2004, with the epicenter off the west coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. […]

FCTC and Tobacco Control Policies in Southeast Asia: the “Special” Case of Indonesia

Andika Putra, Research Intern at ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada Tobacco is one of the greatest emerging health disasters in human history[1], it’s generally use among the poor and […]

Year of Laos: Queries for the New ASEAN Chair

Habibah Hermanadi, Intern Staff ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada The role of ASEAN chairmanship will be held in the hands of Laos in 2016; despite the fact that it […]

ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution: The Indonesian Commitment

Andika Putra, Intern staff at ASEAN Studies Center UGM Indonesia has finally ratified the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution (AATHP) on September 2014. After 12 years, the ratification was […]

ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC) dan Dialog Antar-Agama: Sebuah Tinjuauan Kritis

Dedi Dinarto, Asisten Riset Pusat Kajian ASEAN UGM Berakhirnya tahun 2015 menjadi titik awal bagi integrasi masyarakat ASEAN yang menekankan aspek ‘people-centered’ sebagai fokus baru di kawasan. Beberapa dokumen ASEAN telah memasukkan istilah ini dengan tujuan […]

Japan-Philippines Defense Pact May Worsen South China Sea Tension

Dedi Dinarto, Research Assistant at ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada On February 29, 2016, the signing of a defense pact between Japan and the Philippines confirmed as a strategic […]

Malaysia’s Foreign Policy: Where Malaysia Stands and What It Means

Photo source: https://ripplesoftruth.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/kuala-lumpur-25.jpg Habibah Hermanadi, Intern staff ASEAN Studies Center UGM In 2012, The Edge Malaysia published a concise explanation regarding Malaysia’s position and how it sees ASEAN. It stated that […]

Mahathir, Identitas, dan Masa Depan ASEAN

Photo source: http://www.katariau.com/foto_berita/16Mahathir%20Muhammad.jpg Dedi Dinarto, Asisten Riset ASEAN Studies Center UGM Beberapa menit yang lalu, saya menutup lembar terakhir dari sebuah otobiografi mantan Perdana Menteri Malaysia, Mahathir Mohamad. Bacaan tersebut […]

Questioning ASEAN’s Legitimacy from Its Charter

Dio Herdiawan Tobing, Intern Staff at ASEAN Studies Center UGM Not to be surprised anymore that each of ASEAN member states are given veto power to reject Draft Communique which […]

The United Nations World Conference for Disaster Risk Reduction: The ASEAN Commitment

Mohammad Arumbinang, Intern staff at ASEAN Studies Center UGM Throwback in 1990’s, as remembered as the declaration of the international decade for natural disaster reduction. Nowadays, disaster risk is increasingly […]

Report on Progress: 100th days of ASEAN Economic Community

Habibah Hermanadi, Intern Staff ASEAN Studies Center UGM Last Monday, 11th of April 2016 marked the 100 days of the establishment of ASEAN Economic Community. From this point it is […]

Natural and Man-made Disaster Relief as Soft Diplomacy between ASEAN States and Other States

Photo credit: http://writingserviceiya.dynu.net Mohammad Hazyar Arumbinang, Intern staff ASEAN Studies Center UGM During the past decade, natural and man-made disasters at various scales continue to increase by the year in […]

ASEAN Economic Community: Road to a Community Friendly Economic Integration

Habibah Hermanadi, Intern staff at ASEAN Studies Center UGM The road to a complete economic integration promoting higher productivity and trade activity for ASEAN is filled with challenges and opportunities. […]

A People-Centered ASEAN without Human Rights Regime

Dio H. Tobing, Intern Staff at ASEAN Studies Center UGM ASEAN is always at risk when there is a call to faithfully implement human rights values within Southeast Asian Region, […]

Rethinking the Role of ICSID in Investor-State Dispute Settlement in ASEAN Economic Community

Andika Putra, Intern Staff at ASEAN Studies Center UGM The establishment of ASEAN Community aims to improve the welfare of all ASEAN member states to be able to compete in […]

Public Lecture: Women, Development and Environmental Justice

Public Lecture: Women, Development and Environmental Justice. Speakers: Prof. Kim Eun Shil (Professor, Women’s Studies and Director of Korean Women’s Institute, Ewha Womans University) Dr. Phil Dewi Candraningrum (Chief Editor […]

Indonesia’s Foreign Policy and the Changing Global Architecture

Ahmad Rizky Mardhatillah Umar (Researcher at ASEAN Studies Center UGM) studies Politics with Research Methods at the University of Sheffield, UK. Muhammad Rosyidin’s article in the October-December 2015 edition of Strategic […]

Seminar dan Bedah Buku: UKM dalam Pusaran Masyarakat Ekonomi ASEAN

Seminar Nasional: UGM Menghadapi Masyarakat Sosial dan Budaya ASEAN: Tantangan, Strategi, dan Prospek Kebijakan

Seminar ini bertujuan untuk menelaah, secara lebih mendalam, hubungan antara mobilitas kawasan yang terbentuk dalam kerangka Masyarakat ASEAN dengan kebijakan pendidikan tinggi di Indonesia. Dalam desain Masyarakat Sosial dan Budaya […]

Can the Subaltern Speak in ASEAN?

Ahmad Rizky M Umar, Postgraduate Student at Department of Politics, University of Sheffield and formerly a Research Assistant at ASEAN Studies Centre, Universitas Gadjah Mada Can the subaltern speak? Gayatri […]

Talkshow: Meninjau Keuniversalan Gerakan Sosial di ASEAN

Perbincangan mengenai gerakan sosial kerap terhubung dengan cita-cita para negara anggota ASEAN yang dalam waktu yang singkat ini akan mengimplementasikan Komunitas ASEAN 2015 sebagai babak baru kehidupan politik, ekonomi, dan […]

Workshop: Championing Your Business in ASEAN Community

Is Jokowi Turning His Back to ASEAN?

Dr. Avery Poole Lecturer at the School of Social and Political Sciences, the University of Melbourne and 2013 Visiting Fellow at ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada Under President […]

ASEAN dan Penanggulangan Terorisme: Beberapa Catatan

Oleh Agung Hidayat, Staf Intern di ASEAN Studies Center UGM, Mahasiswa Ilmu Komunikasi UGM Aksi ektremisme, terorisme serta militansi Islam menjadi ancaman nyata bagi keberagaman masyarakat ASEAN. Baru-baru ini, kasus Islamic […]

ASEAN People’s Forum 2015: Menuju ASEAN yang People-Centred dan People-Oriented?

Nitia Agustini, Research Intern di ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada Salah satu isu penting yang agak terabaikan dalam perkembangan Masyarakat ASEAN dewasa ini adalah keterlibatan Masyarakat Sipil di […]

Refugee Crisis Meeting Should Learn from Indochinese Solution

Atin Prabandari, Researcher at ASEAN Studies Center and Lecturer at Department of International Relations, Universitas Gadjah Mada Representatives from 17 countries and three international organisations meeting in Bangkok to […]

Masyarakat Ekonomi ASEAN dan Tantangan Reformasi Birokrasi

Muhammad Prayoga Permana, MPP Kepala ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada Masyarakat Ekonomi ASEAN (selanjutnya disingkat EA) akan segera diluncurkan akhir tahun 2015 ini. Disadari atau tidak, MEA akan sangat […]

A Paradox of Multitrack Diplomacy

Ahmad Rizky Mardhatillah Umar, Researcher at ASEAN Studies Center UGM In 1996, John MacDonald and Louise Diamond wrote the book, Multi-track Diplomacy, which promoted the role of non-state actors in diplomatic theory. This […]

China and The ASEAN: A Need for Shifting Paradigm

Dedi Dinarto – Research Intern at ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada (dinartodedi@gmail.com) Even though China has successfully controlled the entire Spratlys on January 1974, the discourse on China’s presence […]

Seminar: Peran dan Tantangan G20 bagi Perekonomian Indonesia di Era Pemerintahan Baru

Seminar: Peran dan Tantangan G20 bagi Perekonomian Indonesia di Era Pemerintahan Baru Tempat: Hotel royal Ambarrukmo, Yogyakarta Waktu: Kamis, 7 Mei 2015, 09.00 – 12.00 Pembicara: Toferry P. Soetikno – Direktur […]

What Does Myanmar Student Protests Mean for ASEAN?

Rizky Alif Alvian and Tadzkia Nurshafira Board of Chairman and Head of Advocacy Committee at the Student Council of Faculty of Social and Politicial Sciences, Universitas Gadjah Mada Justice […]

Seminar: Capaian dan Prospek Indonesia dalam Komunitas ASEAN 2015

Malaysia’s Chairmanship and Civil Society Engagement in ASEAN

Ahmad Rizky M. Umar, Researcher, ASEAN Studies Centre, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia As Myanmar’s chairmanship in ASEAN will be ended this year, we are now looking forward to transfer the chairmanship […]

Whither ASEAN Centrality?

Ahmad Rizky Mardhatillah Umar, Research Assistant at ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada The South China Sea dispute has been the main focus of this year’s ASEAN summit, which was […]

ASEAN dan Pemberantasan Korupsi

Ahmad Rizky Mardhatillah Umar, Asisten peneliti di ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada Artikel ini dimuat di Harian Kompas (Siang), 2 Mei 2014 Bisakah ASEAN mendorong pemberantasan korupsi? […]

Seminar – Championing ASEAN Community 2015: Inside Indonesia

Seminar “Championing ASEAN Community 2015: Inside Indonesia” will be held on Thursday, December 11th 2014 at Ruang Seminar MAP UGM, Fisipol UGM Unit II SEKIP, Jalan Prof. Dr. Sardjito, Yogyakarta. The conference […]

Making ASEAN Democratic

Ahmad Rizky Mardhatillah Umar, Research Assistant at ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada ASEAN has held its 24th and 25th Summit in Myanmar this year. The latest Summit has just […]

What Does Jokowi’s “Pro-People Diplomacy” Mean for ASEAN?

By Ahmad Rizky Mardhatillah Umar, research assistant at ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada Foreign Minister H.E. Retno LP Marsudi has launched her first speech on Indonesia’s Foreign Policy in Wednesday […]

A new ASEAN community? Many already live it

By Farish Ahmad-Noor, For The Straits Times It is a question that may strike some as being somewhat simple: Where is Asean? However, the simplicity belies a deeper and more complex […]

ICONAS 2014

International Conference on ASEAN Studies 2014 (ICONAS 2014) will be held on Wednesday-Thursday, October 1st – 2nd 2014 at Inna Garuda Hotel, Jalan Malioboro, Yogyakarta. The conference will be started at 09.00 […]

Making ASEAN Works in Rohingya: A Southeast Asian Perspective

Ahmad Rizky Mardhatillah Umar Research Assistant at ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada Rohingya has become the most ironic phennomenon in Southeast Asia. Since 1990s, they have been exiled, […]

Workshop MEA untuk Pemerintah Daerah

“Kesiapan Pemerintah Daerah Dalam Menghadapi Masyarakat Ekonomi ASEAN 2015” Waktu: 18-20 Juni 2014 Tempat: Jogja Plaza Hotel, Yogyakarta Dihadiri oleh 30 perwakilan dari beberapa pemerintah daerah di Indonesia, perwakilan dari […]