Colonialism Beneath Protectionism: The Trade Disputes Between Indonesia and the European Union

Author: Daniel Situmeang Since the mid-20th century, many developing countries have been freed from the shackles of European colonial rule. Indonesia itself has been recognized as an independent state by […]

Unveiling Power Politics Behind Najib’s “Red-Carpet” Legal Treatment

Author: Aldi Haydar Mulia Photo by Bernd Dittrich on Unsplash In Malaysia, another twist to the tale of the convicted ex-Prime Minister, Najib Razak, has developed yet again. The Court […]

The Shift in Japan’s Economic Strategy with ASEAN: Why Domestic Matters

The year is 1974. Sakura season hasn’t come yet. Only the cold breeze from the north covers Japan with snow. At that time, Japan’s PM, Tanaka Kakuei, flew to a […]

Forgotten: ASEAN’s Vision on Disaster Management

It was merely three months ago when Indonesians headed to the polls to elect their municipal leaders in the 2024 local elections. As many as 207 million eligible voters were […]

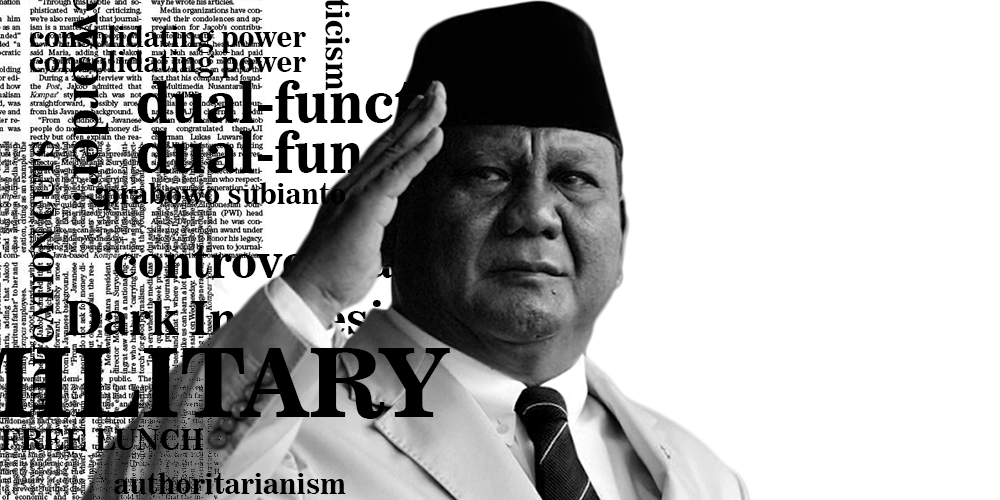

The Getaway Car Presidency: Prabowo, Power, and the Road to Nowhere

Drivin’ the getaway car We were flyin’, but we’d never get far Taylor Swift’s Getaway Car is a song about high-speed betrayals, thrilling escapes, and the eventual realization that running from one […]

ASEAN Studies Center – Japan Foundation Essay Competition

Background The Indo-Pacific region faces a complex and evolving landscape of strategic, economic, and security challenges. While Japan and ASEAN have maintained a longstanding partnership characterized by cooperation in areas […]

“Mapping the Critical Role of ACWC, CSOs, and Academia” and “ASEAN Post-2025 Vision Consultation”

A seminar titled “Mapping the Critical Role of ACWC, CSOs, and Academia” was held on November 1, 2024, at The Manohara Hotel Yogyakarta, Indonesia. This landmark event provided a significant […]

Policy Brief Competition

Top 3 Policy Briefs First Place – “Collaborating Youth Power for Child and Women Protection from Online Gambling Risks in ASEAN Countries”, by Muh. Rifki Ramadhan, Bagas Febi Cahyono, and […]

Public Lecture on “Navigating Contemporary Challenges: Indonesian Diplomacy in a Chanching Global Changes”

On September 12, 2024, the ASEAN Studies Center of Universitas Gadjah Mada and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia held a public lecture entitled “Navigating Contemporary […]

ASEAN Studies Center welcomed a visitation from Prof. Kimikazu Shigemasa from Kwansei Gakuin University, Japan

ASEAN Studies Center welcomed a visitation from Prof. Kimikazu Shigemasa from Kwansei Gakuin University, Japan on 11-12 September 2024. The discussions during the visit revolved around significant topics, including developments […]