Time to Prepare Rowing between Two Great Islands Again

Since the mid of September 2021, there has always been news and columns about AUKUS in the mass media headlines. AUKUS, the trilateral military cooperation between Australia, the UK, and the USA would drive Australia to have nuclear-powered submarines in the next few years. Despite nuclear power being used as the power source of the submarine, it’s undeniable that nuclear-powered submarines would strengthen Australia’s navy capability significantly.

AUKUS is also believed to have violated the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in the Pacific region. Furthermore, it will trigger China to increase its military capabilities and lead it to cold-war 2.0, or even an open conflict in the region. The partnership would also strengthen the US presence in the Asia-Pacific region since the US formed an alliance named QUAD with India, Japan, and Australia in 2017 that has the most developed military capacity in the Asia-Pacific region excluding China. Hence, China would be surrounded by the allies of the USA in the South, East, and the Southwest. On the other hand, China only has Russia as its traditional ally in terms of security in the North. For China, it has no option other than to strengthen its military capacity to balance the USA and its allies in the Asia-Pacific region.

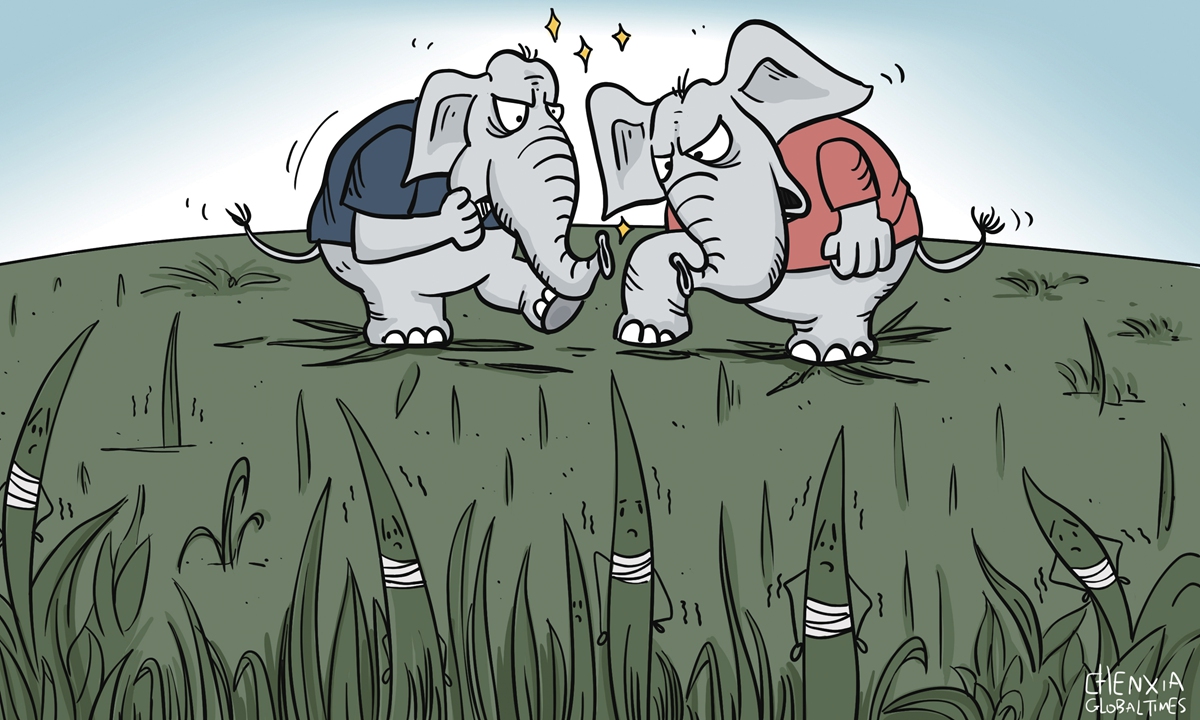

If the cold war or open conflict occurs between China and the USA and its allies, the arena would be in Southeast Asia as it is located between China and Australia. ASEAN countries are inferior compared to China, the USA, or Australia with their future nuclear-powered submarines. To describe this situation, Global Times published a fairly accurate illustration of the possibility of conflict in the Southeast Asia region. The Illustration depicts US-Australia and China as two elephants who are fighting on the grass. Meanwhile, the ASEAN countries are portrayed as the broken grass that receives the consequences of the battle between two countries plus Australia. From the illustration by the Global Times, we can assume that ASEAN countries will be adversely affected by the confrontation of the USA-Australia versus China.

Illustration by : Chen Xia/Global Times

It will be quite possible for ASEAN to get trapped in the security dilemma. Moreover, the security integration of ASEAN members is still relatively low compared to the EU, and its member states are far from standing on common ground in terms of diplomatic and defense policies. It is difficult for ASEAN member states to rely on the collective defense of ASEAN to seek collective security. They can only rely on independent military capacity-building and appropriate and independent diplomatic strategies. However, the military strength of ASEAN member states still seems incomparable to the military power of the USA, China, or even Australia with its future nuclear-powered submarines. The data published by the World Population Review shows that by 2021 ASEAN only has 14 submarines in total, of which six of them are owned by Vietnam, two units belong to Malaysia, one submarine from Myanmar, and five other submarines belong to Indonesia. This is such a crushing defeat where China has 74 and the USA has 66 submarines which are clearly more than the total number of submarines that ASEAN countries currently have. AUKUS will lead Australia to have more advanced submarines, which consequently will outperform ASEAN countries if they do not increase their military capacity. As a response to the possible security threats, the most viable action to do by each ASEAN member state is to strengthen their military capacity to secure their security. ASEAN should also strengthen its security integration in responding to AUKUS and the possibility of open war in the region.

Besides the military capacity, ASEAN centrality will also be tested by AUKUS. Each ASEAN member state shows different reactions towards the AUKUS. Ismail Sabri Yakob, the Malaysian Prime Minister expresses his concern on how AUKUS may possibly provoke other powers to act more aggressively in the region, especially in the South China Sea. Similar to Malaysia, the Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi emphasized that none of the ASEAN countries intends to intensify arms race and power projection in the region, which of course will threaten regional security stability. However, unlike Indonesia and Malaysia, the Philippines has shown its support for the formation of AUKUS in the region. A favorable statement was also stated by Singapore’s PM Lee Hsien Loong, that AUKUS would contribute constructively to the peace and stability of the region and complement the regional architecture. By the responses of Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines, we can conclude that ASEAN countries have not been able to unite their voices in responding to the AUKUS cooperation. It is a result of the demand for protection and cooperation with the USA and different perceptions of China as a threat as well as a partner. On the one hand, China is one of the most strategic trade partners for ASEAN. China’s bilateral trade to ASEAN reaches 684 billion USD in 2020. On the other hand, China is also a threat to the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Brunei Darussalam. Thus, it is difficult for the ASEAN to take a common position over AUKUS.

Despite their different position in dealing with AUKUS, ASEAN member states made it clear that they refuse to take sides. As Singapore’s Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan said, Southeast Asia wants peace and prosperity, reiterating a long-time stance that countries are against being forced to take sides in the US-China rivalry. If we go back to the past, the cold war was the reason for the ASEAN establishment in 1967. Five founding fathers countries of ASEAN gathered themselves in order to unite their “power” and avoid the cold war involvement. It was like, ASEAN rowing between two great islands in the past. The regional circumstances nowadays are different compared to how Southeast Asia was 54 years ago, which can be seen through how ASEAN countries seem more integrated now. Furthermore, ASEAN weaves the partnership with China, Australia, and the USA through the ASEAN+ mechanism. Therefore, the doors for dialogue are always open to prevent the bad scenarios related to the AUKUS. However, along with the possibility of the cold war 2.0 between China and the USA, ASEAN must be prepared for rowing between two great islands again for the second time.

About Writer

- Lucky Kardanardi is a Programme intern at ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada. Lucky is also an associate writer of The Bridge Magazine. He holds the bachelor’s degree of Social Sciences majors in International Relations with particular focuses on Southeast Asian and European studies.