Questioned Centrality: Will ASEAN Stand Stronger in the South China Sea?

Written by Rahina Dyah Adani, University of Gadjah Mada (picture: Reuters) The unimproved situation in the South China Sea has questioned ASEAN’s so-called ‘centrality’ in security of the region. The association is said to be more divided in regards to the South China Sea dispute as U.S. and China have divided the group by working […]

Questioning Digital Integration via E-Commerce as New Force of Regional Integration

Written by Muhammad Rasyid Ridho, a Graduate Student of International Relations Universitas Gadjah Mada. ABSTRACT The newest ASEAN Leaders’ Vision encompasses e-commerce as its underlined issue. As its relevancy is in line with the ascendancy of Industrial Revolution 4.0, it has potential as a new track of regional integration. It is inferred that ASEAN […]

The Battle Against Trafficking in Persons: Is ASEAN Heading in the Right Direction?

Written by Firstya Dizka Arrum Ramadhanty, International Relations Undergraduate Student, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Gadjah Mada In the last two decades, ASEAN’s battle on acknowledging the increasing trend of transnational crimes and human rights and security matter has been interesting to look at. Progress have been considerable. In 2004, there was […]

Strengthening ASEAN’s Political-Security Pillar through Pool of Sovereignty

Written by Turin Airlangga, student at the Graduate School of Asia Pacific Studies (GSAPS), Waseda University Tokyo, Japan. He can be reached atturin.a@fuji.waseda.jp Abstract ASEAN as an entity and Southeast Asia as a region emerged as important key players in the global political landscape after 51 years of its establishment. Economic growths and prosperity has […]

ASEAN Agreement on E-Commerce: What It Tries to Tackle

By Robbaita Zahra The OECD defines e-commerce as “the sale or purchase of goods or services, conducted over computer networks by methods specifically designed for the purpose of receiving or placing orders. The goods and services are ordered by those methods, but the payment and ultimate delivery of the goods or services do not have […]

Reforming North Korea’s economy: What role for ASEAN?

Shah Suraj Bharat/Jakarta Photo by Uri Tours (Wikipedia) The peace process between the two Koreas is exactly– a peace process – something that has eluded the peninsula after 70 years of hostility. Investors, policymakers and the international community will have to be patient on the potential for market reform in North Korea. Yet, there is […]

The Indo-Pacific Affairs: Between India’s Ambitions and ASEAN’s Position

Habibah H. Hermanadi – Research Associate to Institute of International Studies and Post-graduate candidate from University of Delhi India imagined a larger role beyond its current dominance in South Asia, the Act East Policy had become a known concept subject to the discussion under foreign policy context. When India reaches Southeast Asia, it becomes clear […]

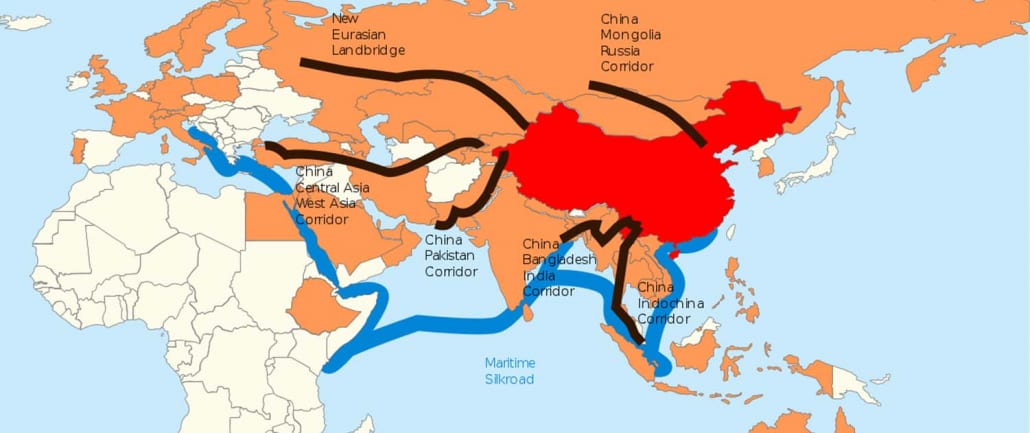

The Tightening Belt Around ASEAN’s Narrowing Road to Success

By Matthew LoCastro, illustration by Lommes (Wikipedia) The Belt and Road Initiative within ASEAN The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also known as One Belt One Road (OBOR), is one of the most prominent and one of the most shrouded global development initiatives in modern history. With estimated investments of about US$150 billion over the […]

Decoding the Indo-Pacific outlook

See original post in Bangkok Post The 34th Asean Summit wrapped up last week in Bangkok, with the adoption of a crucial document known as the Asean Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP). Prime Minister, Gen Prayut Chan-o-cha, regarded the AOIP as a milestone as the bloc now has a unified perspective on how to deal […]

Indonesia’s Journey to Reduce 70% of Marine Waste by 2025

by Carter Anne Jones* Pictures: Forest and Kim Starr Indonesia produces 3.2 million tons of mismanaged trash ever year with nearly 1.3 million tons ending up in the sea. This makes Indonesia the second-largest plastic polluter after China. Last year, Bali declared a trash emergency and used 700 cleaners to collect nearly 100 tons of […]