The Tightening Belt Around ASEAN’s Narrowing Road to Success

By Matthew LoCastro, illustration by Lommes (Wikipedia)

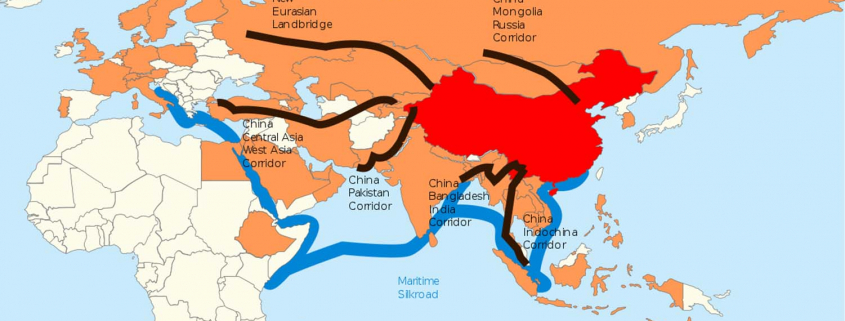

The Belt and Road Initiative within ASEAN

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also known as One Belt One Road (OBOR), is one of the most prominent and one of the most shrouded global development initiatives in modern history. With estimated investments of about US$150 billion over the next decade with a total price tag ranging from US$1trillion to US$4 trillion, BRI still remains only a singular part of China’s larger desire to invest, connect, and craft a sphere of influence, or as President Xi describes it, “a community of common destiny,” across Asia.

As of 2018, China has funded 96projects across South East Asia. China’s projects, a variety of roads, railroads, ports, power plants, and other infrastructure projects have provided insight into China’s grand strategy. ASEAN member states will have to determine if China’s investments and influence will support or disrupt ASEAN’s commitments to resiliency and innovation within the realm of its socio-cultural, economic, and political/security pillarsoutlined in the ASEAN 2025: Forging Ahead Together. As with many investment and economic development initiatives, ASEAN members can expect tangible benefits aligned with the ASEAN development framework but should ultimately air caution to China’s advances due to long term and deeply embedded costs.

A Positive Outlook for the BRI

China’s BRI and larger foreign investment goals have the potential to bolster the ASEAN 2025 vision. China has been a leader in poverty alleviation within its own boarders, uplifting 800 million people out of poverty since the 1980’s with the goal of eliminating all domestic extreme poverty by 2020. China’s success has the potential to carry across ASEAN as investments lead to job creation and infrastructure development, and consequentially reducing spatial inequality.

The potential for successful investment impacts are further supported by a 2018 study conducted by The Brookings Institute. Brookings evaluated the national economic impacts of approximately 4,300 Chinese government financed development projects in 138 countries and found that on average, Chinese aid and investment yielded economic growth dividends. For the average host country, a doubling of Chinese official development assistance produced a 0.4% point increase in economic growth two years after the funding was approved.

Reducing inequality, ensuring equitable economic growth, and developing an interconnected ASEAN that can effectively and easily trade goods and services are accomplishments that fall within the ASEAN 2025 vision. By evaluating the benefits of China’s investments, policymakers can be convinced to welcome BRI funding with open arms. However, it is important to recognize that China’s ambitions do not remain in a silo of intentions to promote regional economic growth. China’s larger goal is to strengthen its international influence. Such a goal will come at a cost to ASEAN’s socio-cultural, economic, and political and security pillars and negate the economic benefits incurred by these investments.

The Adversarial Nature of the BRI and ASEAN’s Three Pillars

The ASEAN socio-cultural pillar states that it is a pivotal goal for ASEAN members to promote equitable access to quality opportunities and to protect human rights. BRI financing is not beholden to these standard. Other institutions, such as the IMF and the World Bank Group, will limit financing to causes that may violate the human rights of an ASEAN member country’s citizens. The BRI allows an option to seek financing from a source that does not abide to a standard of respecting human rights. This outlet inherently undermines that drive and motivation for all member countries to strive to uphold the same obligation. It can be more cost effective or convenient to ignore universally agreed upon standards of human rights when there are limited consequences. This issue is further compounded by the appeal of the ease in structuring financing and receiving funds from China.

China’s investments have also been linked to instances of supporting local corruption, degrading the environment, and weakening trade union participation.

In a 2016 case study of Chinese investment in Africa, empirical results consistently indicated more widespread local corruption around active Chinese project sites. This corruption would linger after the project implementation period, seemingly not driven by an increase in economic activity, but rather signifying that the Chinese presence impacts norms.

Chinese investments also do not have an incentive to support the development of renewable infrastructure or low-carbon investments. As China aims to achieve its own sustainability goals, locating financing for high-carbon projects internationallyallows for China to take credit for emission reduction and environmental quality improvements when in reality the environmental damage is occurring abroad.

Among the projects that BRI supports, researchers have also found a tendency for China to maintain control over development projects throughout the entire implementation phase, using Chinese contractors for work performed in the recipient countries. These contract workers weaken the ability of trade unions to advocate for reasonable labor protections and decrease the overall economic benefits received by locals.

Despite promises of potential economic growth, the economic pillar of the ASEAN 2025 framework is also threatened by BRI investments. Chinese banks are worried about the safety of current lending. Since 2015, commercial banks have cut new BRI financing. Furthermore, China is finding it hard to identify profitable projects in belt-and-road countries leading to BRI being commonly referred to as “One Road, One Trap” amongst the business community.

The investment environment is further complicated by the lack of investment transparency and at times, predatory nature of investments. Chinese backed projects have a uniform contractor base. 89% are Chinese companies, 7.6% are local companies from the country of investment, and 3.4% are foreign companies, non-Chinese companies from a country other than the one where the project was taking place. Compared to multilateral development bank funded projects, 29% are Chinese, 40.8% are local, and 30.2% are foreign.China’s investment strategies also provide little room for local organizations to secure contracting opportunities. The lack of contract diversity coincides with the lack of project transparency preventing ASEAN members from understanding the investment activities occurring in the market and discouraging investment.

Several of China’s infrastructure investments, though not the majority of infrastructure investments, have also been labeled as “debt-traps.” A debt-trap occurs when China finances projects on unfair and unequal terms taking advantage of lower income countries financial needs. The trap component occurs when payment deadlines approach and the borrowing country is no longer able to pay its debts.This leads to Chinese intervention to gain control over the physical assets or gain some other distinct advantage to collect on what they are owed.

In Sri Lanka, the Hambantota Port project fell victim to this scheme. Upon striking a deal with a Chinese state-owned enterprise, Sri Lanka borrowed $307 million from the Chinese Export-Import bank, then $700 million, and finally, $1 billion. Once Sri Lanka found itself unable to pay these loans back, it ceded control and sovereignty of the port to China under a 99-year lease agreement.Similar instances of “debt-trap” financing have occurred in Malaysia, the US$20 billion East Coast Rail Link Project, and in Laos, the China-Laos railway project, among a few examples.

China’s investments abroad have become recognized as attempts to dominate smaller economies. Such actions strip ASEAN members of their economic and political sovereignty. This loss of sovereignty can expand into concerns of security and directly affect the third and final ASEAN 2025 framework pillar of promoting political and physical security.

As seen in Sri Lanka and Laos, there is the potential for vital domestic assets to be under the direct ownership of a foreign entity in the instances of defaulting on project payments or loans. Control over ports and harbors, especially in South East Asia poses a large security threat as the acquisition of these assets could bolster Chinese presence in contested areas such as the South China Sea.

Considering several BRI projects involve maritime infrastructure, China could potentially influence ASEAN member states’ ability to use maritime trade routes and block the development of comprehensive maritime cooperation. Chinese ownership of power plants and access to other supply chains, raw materials and natural resources poses a major security risk in the event of conflict and will increase Chinese soft power over the governance decisions of ASEAN due to this looming threat.

The Need for Caution When Addressing the BRI

As ASEAN member states plan to forge ahead together, it is vital that the 2025 framework for the region takes into consideration the external influences that seek to threaten the ASEAN community. Though investment opportunities from China may appear lucrative, they pose a serious threat to the leadership and success of the ASEAN community. The BRI’s goals are vast and this initiative has the potential to produce a network of infrastructure projects unlike anything the world has yet to see. However, the ambitions and intentions of the BRI must be policy maker’s first consideration. Unlike multilateral development banks and other international financial institutions, China’s intention is not focused on aid and mutual global development. It is driven by a desire to control and dominate the actions of other sovereign nations.

Matthew LoCastro attended Hunter College in New York City and is a Luce Scholar