Colonialism Beneath Protectionism: The Trade Disputes Between Indonesia and the European Union

Author: Daniel Situmeang Since the mid-20th century, many developing countries have been freed from the shackles of European colonial rule. Indonesia itself has been recognized as an independent state by […]

Unveiling Power Politics Behind Najib’s “Red-Carpet” Legal Treatment

Author: Aldi Haydar Mulia Photo by Bernd Dittrich on Unsplash In Malaysia, another twist to the tale of the convicted ex-Prime Minister, Najib Razak, has developed yet again. The Court […]

Forgotten: ASEAN’s Vision on Disaster Management

It was merely three months ago when Indonesians headed to the polls to elect their municipal leaders in the 2024 local elections. As many as 207 million eligible voters were […]

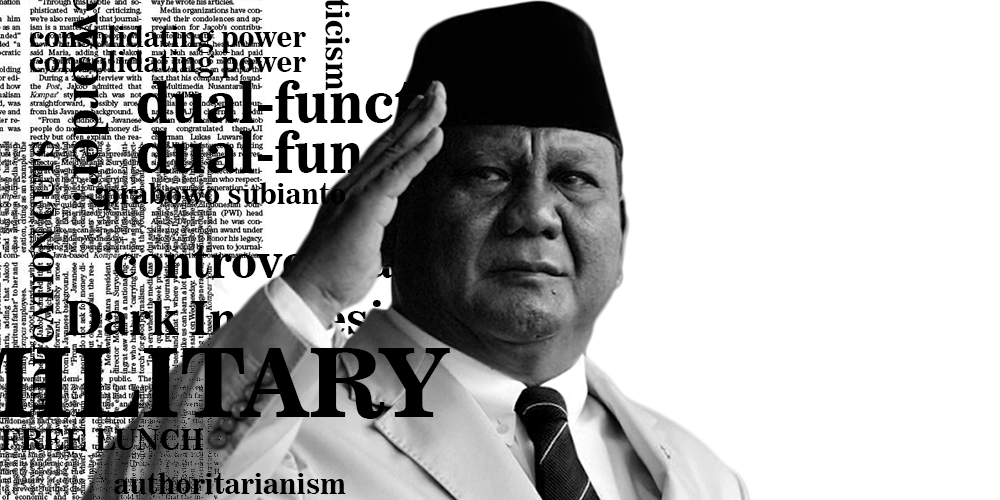

The Getaway Car Presidency: Prabowo, Power, and the Road to Nowhere

Drivin’ the getaway car We were flyin’, but we’d never get far Taylor Swift’s Getaway Car is a song about high-speed betrayals, thrilling escapes, and the eventual realization that running from one […]

RELIGION: BOON OR BANE FOR DEMOCRACY?

In December 2022, the Indonesian government passed a law that penalizes sex outside marriage. This is only one of the many changes in the criminal code that observers warn of […]

Redefining Commodities in International Trade: ASEAN Blue Carbon Initiative and Its Role in Navigating Climate Crisis in the Southeast Asia Region

Stepping further into the technological and industrial advancement age, the narration of sustainability in the international trade system has gained much attention from policymakers worldwide. Not only due to the […]

ASEAN Chairmanship 2023: Indonesia’s Tendency to Solve the South China Sea Territorial Disputes

On 13 November 2022, the handover of ASEAN chairmanship from Cambodia to Indonesia was held at the ASEAN summit. Adopted the “ASEAN Matters: Epicentrum of Growth” theme, Indonesia is responsible […]

Embracing ASEAN Economic Community 2025: Unlocking Prospects and Overcoming Obstacles in Indonesia

Imagine businesses of all sizes, effortlessly trading goods and services across ASEAN borders, tapping into diverse markets, and seizing growth opportunities. Picture investors eagerly exploring investment prospects in ASEAN, fueling […]

ASEAN’s Pathway to Sustainability Through Green Recovery Post-Pandemic Covid-19: Challenge and Opportunity

Written by Wahyu Candra Dewi Striking in 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic has significantly brought disruption to people’s livelihoods worldwide. Upon its initial announcement in March, the pandemic extended from a […]

What’s Missing in the AHRD?: Synergizing with Civil Society Towards Better Human Rights Regime in ASEAN

Written by Gerald John C. Guillermo Civil society has long been a bastion of service and advocacy—contributing to the development and uplifting of lives, particularly in marginalized and underprivileged sectors […]