Press Release Bincang ASEAN “Transnational Activism for Migrant Workers in Asia: The Case of Indonesia and the Philippines”

Yogyakarta, October 26th 2018 Yogyakarta – On Friday, October 26, 2018, ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada held the fourth edition of Bincang ASEAN 2018. Approximately 50 students and practitioners across Yogyakarta, Central Java and West Java registered on this Bincang ASEAN #4 held in BA 201 Room FISIPOL UGM on October 26th, 2018. On […]

Press Release Bincang ASEAN “Delegate Sharing Session: Model ASEAN Meeting Experiences”

Yogyakarta, Friday, October 12, 2018 ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada held its very first collaborated Bincang ASEAN featuring the Department of International Relations, Universitas Islam Indonesia. In order to better raise awareness and promote greater ownership of the ASEAN Community among young generation throughout the region, as well as to introduce more closely how […]

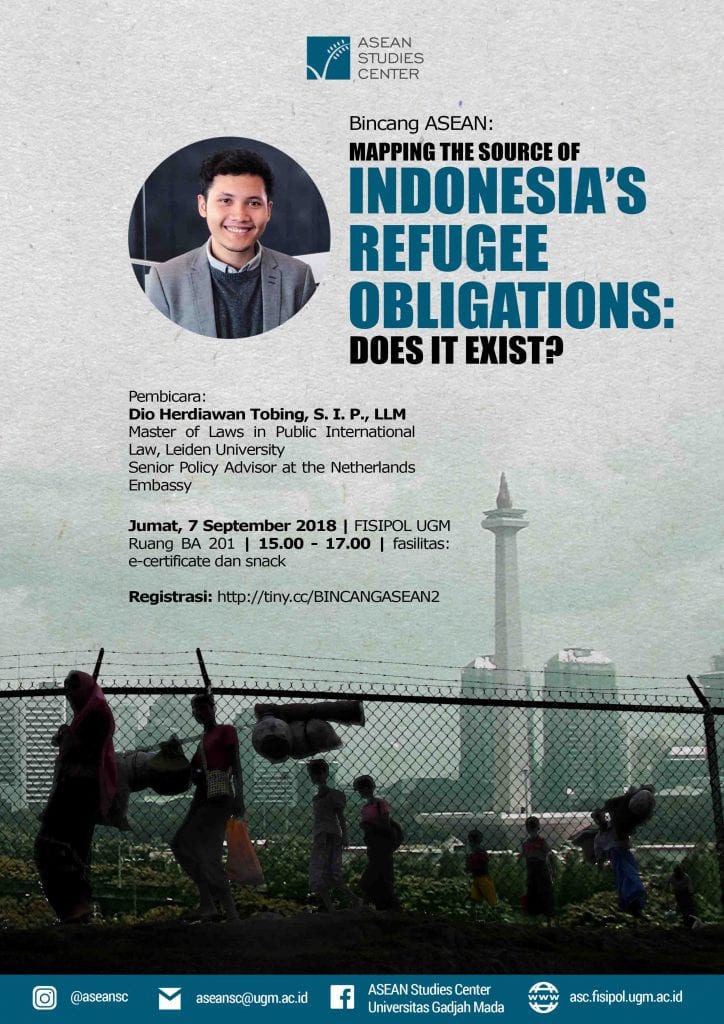

Press Release BINCANG ASEAN “Mapping the Source of Indonesia’s Refugee Obligations: Does it Exist?”

Yogyakarta, 6th September 2018 ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gadjah Mada held the second meeting of Bincang ASEAN in Thursday (6/9), with Dio Herdiawan Tobing S.IP, LLM, former researcher at the ASEAN Studies Center UGM, who is currently working as Senior Policy Advisor at the Netherlands Embassy, presenting his dissertation on “Mapping the Source of […]

Bincang ASEAN: Mapping the Source of Indonesia’s Refugee Obligations: Does it Exist?

[ASC EVENT] Bincang ASEAN With more than 13,000 asylum-seekers and refugees currently hosted in Indonesia, the country is regarded as one of the main refugee transit countries in Southeast Asia after Thailand and Malaysia. However, in light of the situation, Indonesia is a non-party to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its additional protocol. The Foreign […]

Seminar on Enhancement of Cooperation between Eastern Part of Indonesia and Southern Part of the Philippines

Seminar on Enhancement of Cooperation between Eastern Part of Indonesia and Southern Part of the Philippines 23 August 2018 | 8.30 – 16.45 | R. Seminar Timur, Fisipol UGM REGISTRATION until 21 August 2018 ————————- Subject: August Seminar | Format: name_institution_phone number | send to: aseansc@ugm.ac.id CP Karina +62 851 1332 3663 *Registration starts at […]

Press Release BINCANG ASEAN “Democratization in Southeast Asia: The Case of Indonesia, Philippines and Thailand”

Bincang ASEAN Monday, 14 May 2018 Yogyakarta – Recently, the ASEAN Studies Center UGM held its first Bincang ASEAN in 2018 entitled “The Democratization in Southeast Asia: The Case of Indonesia, Philippines and Thailand” at Digilib Café FISIPOL, UGM. This particular Bincang ASEAN featured Hestutomo Restu Kuncoro, M.A. (Alumni of Manchester University) with Ezka Amalia […]

Internship Program

ASEAN Studies Center Universitas Gajah Mada membuka kesempatan magang untuk mahasiswa dari seluruh jurusan di universitas di Yogyakarta yang akan berkesempatan untuk terlibat dalam riset serta program akademik yang diselenggarakan oleh ASEAN Studies Center UGM. Output dari pekerjaan intern adalah sebagai berikut: 1. Membuat artikel mengenai isu-isu ASEAN sebanyak 1 buah, dalam Bahasa Indonesia atau […]

Day 3: UGM-RUG International Working Conference on Regional and National Approaches Toward Sustainable Development Goals in Southeast Asia and ASEAN

The third day of UGM-RUG International Working Conference on Regional and National Approaches toward Sustainable Development Goals in Southeast Asia held on October 5th 2017. With only three session of draft paper presentation left, the international working conference was opened by Dr. Titus C. Chen’s presentation on his draft paper. The title of his work […]

Day 2: UGM-RUG International Working Conference on Regional and National Approaches Toward Sustainable Development Goals in Southeast Asia and ASEAN

The second day of UGM-RUG international working conference on October 4th 2017 was opened by Prof. Dr. Ronald Holzhacker draft paper presentation the relation of multi-level governance and the sustainable development goals. Taking concern on how some persistence issues and also some unfinished agenda from the MDGs, Prof. Dr. Ronald Holzacker then point out at […]

UGM-RUG International Working Conference on Regional and National Approaches Toward Sustainable Development Goals in Southeast Asia and ASEAN Day 1

ASEAN Studies Center, Universitas Gadjah Mada and the Groningen Research Centre for Southeast Asia and ASEAN, University of Groningen, organized international working conference on regional and national approaches toward sustainable development goals in Southeast Asia and ASEAN. The conference was opened by welcoming message from Dr. Dafri Agussalim, MA, as the Director of ASEAN Studies […]